Search results for "haavikko"

The power game

30 June 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Puhua, vastata, opettaa (‘Speak, answer, teach’, 1972) could be called a collection of aphorisms or poems; the pieces resemble prose in having a connected plot, but they certainly are not narrative prose. Ikuisen rauhan aika (‘A time of eternal peace’, 1981) continues this approach. The title alludes ironically to Kant’s Zum Ewigen Frieden, mentioned in the text; ‘eternal peace’ is funereal for Haavikko.

In his ‘aphorisms’ Haavikko is discovering new methods of discourse for his abiding preoccupation: the power game. All organizations, he thinks, observe the rules of this sport – states, armies, businesses, churches. Any powerful institution wages war in its own way, applying the ruthless military code to autonomous survival, control, aggrandizement, and still more power. No morality – the question is: who wins? ‘I often entertain myself by translating historical events into the jargon of business management, or business promotion into war.’

‘What is a goal for the organization is a crime for the individual.’ Is Haavikko an abysmal pessimist, a cynic? He would himself consider that cynicism is something else: a would-be credulous idealism, plucking out its own eyes, promoting evil through ignorance. As for reality, ‘the world – the world’s a chair that’s pulled from under you. No floor’, says Mr Östanskog in the eponymous play. Reading out the rules of a mindless and cruel sport, without frills, softening qualifications, or groundless hopes, Haavikko is in the tradition of those moralists of the Middle Ages, who wrote tracts denouncing the perversity and madness of ‘the world’ – which is ‘full of work-of-art-resembling works of art, in various colours, book-resembling texts, people-resembling people’.

Kai Laitinen

Speak, answer, teach

When people begin to desire equal rights, fair shares, the right to decide for themselves, to choose

one cannot tell them: You are asking for goods that cannot be made.

One cannot say that when they are manufactured they vanish, and when they are increased they decrease all the time. More…

New from the archive

26 March 2015 | This 'n' that

This week, a cluster of pieces from and about left-leaning Tampere, the ‘Red City’ of Finland

The Tampella and Finlayson factories, 1954, Tampere. Photo: Veikko Kanninen, Vapriikki Photo Archives / CC BY-SA 2.0.

Also known as the ‘Manchester of Finland’ for its 19th-century manufacturing tradition, Tampere – or rather the suburb of Pispala – produced two important, and strongly contrasting, writers, Lauri Viita (1916-1965) and Hannu Salama (born 1936). Both formed part of a group of working-class writers who emerged after the Second World War, many of whom had not completed their school careers and whose confidence arose from independent, auto-didactic, reading and study.

To understand the place from which these writers emerged, it has to be remembered that there is more to Tampere than a proud radical tradition. As Pekka Tarkka remembers in his essay, the Reds were the losing side in the Finnish civil war of 1918, and for years afterwards they formed ‘a sort of embattled camp in Finnish society’. History is always written by the winners, and authors like Viita and Salama played an important role in giving the Red side back its voice.

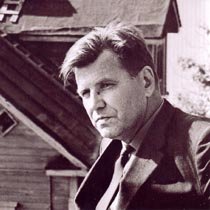

Lauri Viita.

Lauri Viita celebrated Tampere by offering an image of it that is, as Tarkka remarks, ‘poetic, deterministic and materialist’. His poetry differed sharply from the modernist verse of contemporaries such as Paavo Haavikko and Eeva-Liisa Manner, both of whom we have featured recently in our Archive pieces, which abandoned both fixed metres and end-rhymes. His work was an often heroic celebration of the ordinary life of proletarian Tampere, and the more traditional form into which it breathed new life made it accessible. My own mother, for example, who had grown up the child of a Red working-class family far away to the north, in Kajaani, steeped in the rolling cadences of poets such as Aaro Hellaakoski and Uuno Kailas, never really got the hang of Haavikko, or Manner; but she loved Viita.

Here we publish a selection of Viita’s poems, translated by Herbert Lomas, who does an excellent job of capturing his easy-going, unselfconscious rhythms. The introduction is by Kai Laitinen.

Hannu Salama.

Photo: Ptoukkar / CC BY-SA 3.0

Salama is a far more politicised writer than Viita, and he is writing about a Tampere that is already in decline. In his major work, Siinä näkijä missä tekijä (‘No crime without a witness’, 1972), he writes about the travails of the communist minority, doomed to slow extinction – the same band of fellow-travellers to which my grandfather in Kajaani belonged. My mother wasn’t a Salama fan, though – I think his Tampere wasn’t beautiful, or heroic, enough. As someone who had moved far away, to England, she wanted to celebrate, not to mourn.

Here we publish a short story, Hautajaiset (‘The funeral’), which was written at the same time as Siinä näkijä missä tekijä. It’s an unvarnished account of a Tampere funeral which is, at the same time, the funeral of the old, radical way of life – which, sure enough, has vanished almost as if it never existed. As Pekka Tarkka writes of Salama’s short story and the revolutionary songs which run through it: ‘There will be no more singing of communist psalms, or fantasies of the family and of the revolutionary spirit.’

As Marx didn’t say, all that seemed so solid has melted, irretrievably, into air.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues, with a total of 380 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

New from the archive

26 March 2015 | This 'n' that

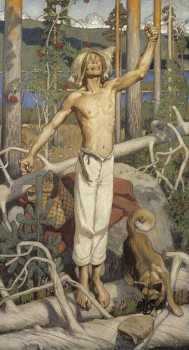

Kullervo’s curse. Painting by Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1899)

Finland’s national epic adapted for the stage by Finland’s national writer: best known as the author of the first significant novel in Finnish, Seitsemän veljestä (Seven Brothers, 1870), Aleksis Kivi (1834-1972) also turned one of the Kalevala’s grimmest stories, that of Kullervo – a tale of incest, revenge and death– into a five-act tragedy.

The translation is by one of Books from Finland’s most long-standing collaborators, David Barrett (1914-1998), a true linguistic genius with a speciality in Georgian as well as Finnish in addition to classical Greek; as well as his work with texts in Finnish and Georgian, he made extensive translations of Aristophanes for Penguin Classics. Barrett felt, as he argues here in his introduction, ‘that Kullervo, if suitably translated, might succeed where Seven Brothers had failed, in bringing Kivi’s genius to the notice of the English-speaking world’.

Was he right? It is up to you, dear readers, to judge.

For a very different, demythologized, view of the Kullervo story, we also publish a manuscript by the modernist poet Paavo Haavikko (1931-2008) from his television adaptation Rauta-aika (‘Age of iron’, 1982).

The Kalevala is in development as a film by the Finnish entertainment company Rovio, of Angry Birds game, and the Finnish-born video game company Supercell. It remains to be seen how the Kalevala take to the big screen.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues, with a total of 372 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Older and wiser?

9 October 2012 | This 'n' that

Illustration: Virpi Talvitie (from Täyttä päätä. Runoja ikääntyville, ‘Full steam ahead. Poems for ageing people’, edited by Tuula Korolainen and Riitta Tulusto)

Nobody can claim that old age is hot, or media-sexy. Yes, but what are older people really like? Are they the bingo-obsessed grannies in floral frocks or old geezers living in the past of popular opinion?

No longer. In just a few years the baby-boom generation will be entering their seventies, when ‘old age’, in its current Western definition, begins. (Until then, senior citizens are allowed to remain ‘adults’.)

Are the old people’s homes ready for them? This new elderly generation will be wanting to listen to Elvis, the Rolling Stones and the Beatles rather than the tango. More…

New literary prize

6 May 2011 | In the news

A new literary prize was founded in 2010 by an association bearing the name of Jarkko Laine (1947–2006) – poet, writer, playwright, translator, long-time editor of the literary journal Parnasso and chair of the Finnish Writers’s Union.

The Jarkko Laine Literary Prize will be awarded to a ‘challenging new literary work’ published during the previous two years. The jury, of nine members, will announce the winner on 19 May.

The shortlist for the first prize is made of Kristina Carlson’s novel Herra Darwinin puutarhuri (‘Mr Darwin’s gardener’, Otava, 2009), Juha Kulmala’s collection of poems, Emme ole dodo (‘We are not dodo’, Savukeidas, 2009) and Erik Wahlström’s novel Flugtämjaren (‘Fly tamer’, Finnish translation Kärpäsenkesyttäjä, Schildts, 2010).

The prize money, €10,000, comes jointly from the publishing houses Otava, Otavamedia and WSOY, the Haavikko Foundation, the City of Turku and the University of Turku.

Kullervo’s story

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Paavo Haavikko wrote this manuscript for the television series Rauta-aika (‘Age of iron’), broadcast in 1982. lt also appeared as a book in 1982, complemented by Kullervon tarina (‘Kullervo’s story’ ) which had been omitted from the original. The text follows the stories of the Kalevala, but they are given a new interpretation: the characters are demythologised, they resign themselves to their fates – they are like ourselves. These extracts are the final scenes in which incest, revenge and death appear in a slightly different guise from Kalevala, or Kivi’s Kullervo.

– Mother, on the road I met your daughter, who is my sister, and took her into my sleigh. She had broken one of her skis. Spring came in one day, the clouds in front of the moon tore themselves to shreds so that two moons passed in one night. Winter went, Spring came, I brought the sleigh back, and I slept on top of the sacks so that not a single grain or seed would be lost. It’s all in the sacks now, saved. The clouds tore off their clothes and washed them in the rivers of rain, and naked, in the dark, they waited for their clothes to dry, those clouds. They even darkened the moon, they would have killed it if they could have reached that far, as it spied on the cloud women who were washing the clothes they had taken off in the waters of heaven, and two moons passed in one night, Kullervo says to his mother, piling up lies like a little boy. Many words. More…