Search results for "Что такое архетипы коллективного бессознательного больше в insta---batmanapollo"

Can’t say it’s not spring

18 April 2013 | Fiction, Prose

Short prose from Mahdottomuuksien rajoissa. Matkakirja (‘In the realm of impossibility. A travel book’, Teos, 2013). Texts by Katri Tapola, illustrations by Virpi Talvitie. Interview by Anna-Leena Ekroos

The first try

A reader doesn’t have to understand anything on the first try. You can always put a book aside and see if the second read will help. If the second, third, fourth, or even fifth read doesn’t help, that’s still all right. What is this constant compulsion to understand everything? There’s nothing wrong with not understanding – on the contrary, it is precisely the state of baffled befuddlement that hides the hope of light within it. I can’t understand any of this! I’m having fun! the reader happily exclaims, and goes on with his life, eyes overflowing with light. More…

Daddy’s girl

30 September 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Maskrosguden (‘The dandelion god’, Söderströms, 2004). Introduction by Maria Antas

The best cinema in town was in the main square. The other was a little way off. It was in the main square too, but you couldn’t compare it to the Royal. At the Grand there was hardly any room between the rows, the floor was flat and there was a dance-hall on the other side of the wall, so that Zorro rode out of time with waltzes, in time with oompahs, out of time with the slow steps of tangos and in time with quick numbers. The Royal was different and had a sloping floor.

Inside, the Royal was several hundred metres long. You could buy sweets on one side and tickets on the other. From Martina Wallin’s mum. She was refined. So was everyone except us: Mum, Dad and me. More…

Bitter moments, luscious moments

31 March 2004 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Fänrik Ståls sägner (Tales of Ensign Stål, 1848–1860) and Dikter II (‘Poems II’. 1833), translated by Judy Moffett. Introductions by Pertti Lassila and Risto Ahti

Sven Duva

Sven Duva’s sire a sergeant was, had served his country long,

Saw action back in ‘88, and then was far from young.

Now poor and gray, he farmed his croft and got his living in,

And had about him children nine, and last of these came Sven.

Now if the old man did, himself have wits enough to share

With such a large and lively swarm – to this I cannot swear;

But plainly no attempt was made to stint the elder ones,

For scarce a crumb remained to give this lastborn of his sons. More…

Briefcase man

31 December 2000 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Aura (Otava, 2000). Introduction by Mervi Kantokorpi

He was born in the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland the year the world caught fire. He learned to read the year of the revolution, and spoke two languages as his mother tongue border – language and enemy language, as he often used to say. He was proud of only one of his languages; the other, he loved secretly. He spoke one loudly, the other softly, almost in a whisper.

At night, on the telephone, he spoke far away – you could see it, even in the dark, from his expression, his half-closed eyes sometimes breaking into song. It was so beautiful and soft that I wept under the blankets and hated myself because of the effect that language had on me.

Stinking tinker Karelian trickster Russian drinker, little Russky’s dancing in a leather skirt, skirt tears and oh! little Russky’s hurt.

Count to ten, he said. But count in Finnish. Or Swedish, that’ll baffle them. And if they call you a Swedish bastard, it’s not so bad. I’ve taught you the numbers in Arabic and Spanish, too, but I don’t think you’ll be able to remember them yet. More…

A roof with a view

27 August 2009 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mistä on mustat tytöt tehty? (‘What are black girls made of?’, Tammi, 2009) Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

I’m a chimney sweep’s daughter, born October 1962 as a gift, a light to a darkened world. I’ve had lots of mothers, but none of them ever stuck around for good. One of them gave birth to me, so she’s Mother, not mother. Her name is Dewdrop, because water has spilled over the only photograph of My Mother and now her face has dissolved into a single translucent droplet; her nose, cheeks and chin are now a fat, shiny blob that looks like it’s about to fall out of the bottom of the picture. More…

Heartstone

2 December 2010 | Reviews

Ulla-Lena Lundberg

‘Knowledge enhances feeling’ is a motto that runs through the whole of Ulla-Lena Lundberg’s oeuvre – both her novels and her travel-writing, covering Åland, Siberia and Africa.

In her trilogy of maritime novels (Leo, Stora världen [‘The wide world’], Allt man kan önska sig [‘All you could wish for’], 1989–1995) she used the form of a family chronicle to depict the development of sea-faring on Åland over the course of a century or so. She gathered her material with historical and anthropological methodology and love of detail. The result was entirely a work of quality fiction, from the consciously old-fashioned rural realism of the first volume to the contradictory postmodern multiplicity of voices in the last – all of it in harmony with the times being depicted.

When Lundberg (born 1947) takes us underground or up onto cliff-faces in her new documentary book, Jägarens leende. Resor i hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’), in order to consider cave- and rock-paintings in various parts of the world, she also reveals a little of the background to this attitude towards life that takes such delight in acquiring knowledge – an attitude that is familiar from many of the protagonists of her novels. More…

Looking back on a dark winter

31 December 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the autobiographical novel Talvisodan aika (‘The time of the Winter War’), the childhood memoirs of Eeva Kilpi. During the winter of 1939–40 she was an 11-year old-schoolgirl in Karelia when it was ceded to the Soviet Union and the population evacuated

Time is the most valuable thing

we can give each other

War’s coming.

One day my father comes out with the familiar words in a totally unfamiliar way, while we’re sitting round the kitchen table eating, or just starting to eat.

He says to mother, as if we simply aren’t there, as if we don’t need to bother, or as if listening means not understanding. Or perhaps they’ve simply no other chance to speak to each other, as father’s always got to be off hunting, or on his way to the station, and mother’s always cooking. More…

Poems

31 March 1979 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Lähdössä tänään (‘Leaving today’, 1977) Introduction by Jouko Tyyri

1

‘The wind’s speaking.’ If the wind were really speaking

could we endure its words

so void, flinty, so groping?

Inside them

they have

salt, horror,

mania: a long-drawn black speechless

roller that wipes the coast clean

of houses, woods, junk. It swashes

your eyes. If I’d had some

feeling. Or thought. If

I was something. If I was I.

It’s gone.

There’s nothing here. Only a draught.

The air moving back and forth, soon to drop.

2

Orlando di Lasso's melodies

airy, without a touch of soil

a little dust on

as much as might be on a butterfly's wing

only just so much

Orlando himself, four hundred years

remoulded into loam, coalesced with dust

just like you, you, just like you More…

The house in Silesia

31 December 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Talo Šleesiassa (‘ The house in Silesia’, 1983). Read the interview

We set off, my brother-in-law and I, at the beginning of September. The tourist season was already over, and on the Gdansk ferry there was stacks of room for my brother-in law’s Volvo and the two of us.

We’d driven from his home on the shore of Lake Mälar to the ferry port at Nynäshamn, about fifty miles south of Stockholm. We’d driven in an atmosphere of cheerful resolution, accelerator down, but going steadily. The resoluteness was due to my brother-in-law’s decision after forty years’ absence to visit his childhood home. If it was still standing, that is – or whatever of it was.

‘Oh the house is definitely still in place there all right,’ he said: ‘I’ve got that sort of tickly feeling in my arse.’ It was a direct translation from the German – German humour of the vulgar variety centring round the bottom. More…

Horse sense

2 February 2012 | Essays, Non-fiction

The eye that sees. Photo: Rauno Koitermaa

In this essay Katri Mehto ponders the enigma of the horse: it is an animal that will consent to serve humans, but is there something else about it that we should know?

A person should meet at least one horse a week to understand something. Dogs help, too, but they have a tendency to lose their essence through constant fussing. People who work with horses often also have a dog or two in tow. They patter around the edge of the riding track sniffing at the manure while their master or mistress on the horse draws loops and arcs in the sand. That is a person surrounded by loyalty.

But a horse has more characteristics that remind one of a cat. A dog wants to serve people, play with humans – demands it, in fact. With a dog, a person is in a co-dependent relationship, where the dog is constantly asking ‘Are we still US?’ More…

All my loving

15 February 2013 | This 'n' that

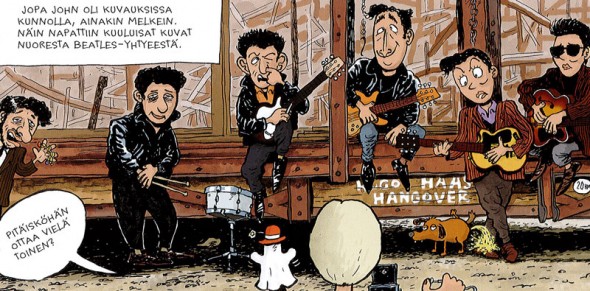

(Early days in Hamburg) Even John behaved himself in the photo sessions, at least almost. This is how the famous photos of the young Beatles were taken.

–Should I take one more? (Astrid the photographer)

One day in the antediluvian times of dawning Beatlemania, a schoolboy in a Finnish small town found himself smitten head over heels by the new pop songs by (probably) the most famous band in the world ever (so far). Like some two billion other teenagers, he learnt by heart every single song the Beatles recorded. Yeah!

The schoolboy grew up and became the illustrator and writer Mauri Kunnas (born 1950), whose storybooks, mostly for children, have now been translated into 30 languages.

But his interest in the Fab Four never left him, and last year he published his illustrated history of John, Paul, George and Ringo, from the day they were born to the day when Please, Please Me / Ask Me Why became number one in the British Top 20 in 1962. As the book is partly written in his native local dialect, its title is Piitles. Tarina erään rockbändin alkutaipaleesta (‘Beatles. The story of the first stage of a rock band’, Otava, 2012).

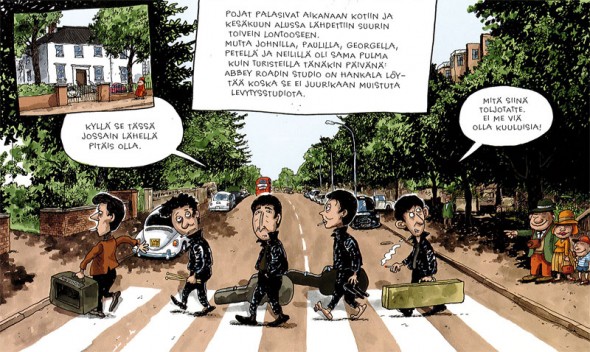

At last the boys came home from Germany, and in June 1962 they left for London with high hopes. But John, Paul, George, Pete and Neil had the same problems that tourists experience even today: The Abbey Road studio is hard to find because it doesn’t look like a recording studio. – It ought to be around here somewhere. – What are you staring at, we’re not famous yet!

In this 77-page graphic story the Beatles grow from babies into celebrities. The large number of hilarious visual details keeps the reader vigilant: for example, in their early days on Hamburg’s Reeperbahn John, Paul, George and Pete (Best) stay in lodgings behind a cinema that are less than hygienic, so on closer examination the lads turn out to be wearing underpants with yellow spots.

–To Eppy! –To my boys!

Julia Lennon, Klaus Voormann, Astrid Kirchherr, Stuart Sutcliffe, Cynthia, Brian Epstein, George Martin: the faces in the gallery of characters are instantly recognisable. Piitles illustrates how Beatlemania was born, and it is truly the work of a faithful fan.