Search results for "2010/02/2011/04/2009/10/writing-and-power"

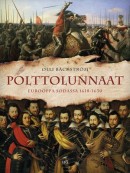

Olli Bäckström: Polttolunnaat. Eurooppa sodassa 1618–1630 [Trial by fire. Europe at war 1618–1630]

31 July 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Polttolunnaat. Eurooppa sodassa 1618–1630

Polttolunnaat. Eurooppa sodassa 1618–1630

[Trial by fire. Europe at war 1618–1630]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura (Finnish Literature Society), 2013. 558 p.

ISBN 978-952-222-394-4

€39, paperback

The Thirty Years War of 1618-48 which ravaged Europe, extending its influence to overseas colonies, has been considered a religious conflict in which several countries were involved for reasons of power politics. Olli Bäckström, who belongs to the younger generation of Finnish military historians, sees the first twelve years of the war as a separate entity that bears similarities to the so-called asymmetric conflicts of our own time, such as those in Africa, which are fought by mercenaries and non-state actors for whom war is an industry and way of life. The book begins by describing the situation in Europe in the early seventeenth century, and the background of the war. Contemporary researchers view it as a religious conflict that originally began in Bohemia and then turned into a political power struggle, but Bäckström sees also the early phase as remarkably nuanced. The Nordic states of Denmark and Sweden (of which Finland was a part) were also in pursuit of fame and power on the battlefields of Central Europe, although Sweden did not really take part in the war until the next phase. Bäckström vividly portrays the alliances formed by the various political actors in order to safeguard their interests, and the methods of warfare employed by the armed forces in the service of the different rulers.

Translated by David McDuff

Star-Eye

31 March 1984 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

A story from Läsning för barn (‘Reading for children’,1884). Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

There was once a little child lying in a snowdrift. Why? Because it had been lost.

It was Christmas Eve. The old Lapp was driving his sledge through the desolate mountains, and the old Lapp woman was following him. The snow sparkled, the Northern Lights were dancing, and the stars were shining brightly in the sky. The old Lapp thought this was a splendid journey and turned round to look for his wife who was alone in her little Lapp sledge, for the reindeer could not pull more than one person at a time. The woman was holding her little child in her arms. It was wrapped in a thick, soft reindeer skin, but it was difficult for the woman to drive a sledge properly with a child in her arms.

When they had reached the top of the mountain and were just starting off downhill, they came across a pack of wolves. It was a big pack, about forty or fifty of them, such as you often see in winter in Lapland when they are on the look-out for a reindeer. Now these wolves had not managed to catch any reindeer; they were howling with hunger and straight away began to pursue the old Lapp and his wife. More…

Journalist 3.0

22 May 2014 | Non-fiction, Tales of a journalist

Illustration: Joonas Väänänen

As the world becomes more and more difficult to understand, the media, strapped for cash and forced for reduce expenses, sack their expert writers. Jyrki Lehtola assesses the new breed of cut-price journalists

Some time in the distant past it was possible for a reader to reflect that here was an educated journalist writing pithily. It would be nice to know more of his or her thoughts.

There used to be talk of such concepts as the ‘objective truth’, and editors shunned talking about themselves, or even speaking or writing in the first person. There was just the world, which the journalist, the conduit of truth, conveyed to the public.

Now, although most of us would prefer to know nothing about journalists and their private lives, journalists have brought their lives strongly into the public arena. Objectivity is dead; there are merely millions of subjects who perhaps share the same experiences, perhaps not, and, misled by some idealised concept of community, we are the beneficiaries of journalists writing about what it’s like to be a mum, how challenging life as a mother and journalist can be. More…

Head in a cloud

27 May 2011 | Articles, Non-fiction

Thinking, reading, writing, buying… Teemu Manninen explores the new freedoms, literal and poetic, offered by cloud computing, where what you can do is no longer limited by what you happen to have on your computer

High in the sky: cumulus clouds. Photo: Michael Jastremski, Wikimedia

I’m sitting in a rocking chair on the porch of a cottage by a lake. My fingers tap and slide on the surface of a black glass panel, a kind of instrument used in the composing of literature. Each tap equals a letter, a series of taps equals a word, a symphony of taps becomes a paragraph, a paragraph an essay.

The glass panel remembers these letters and words and the writings they become, and knows them by their names, but it could also record anything I see or hear. I could even talk to it and it would understand my commands, as if some nether spirit were captured inside, a magic genie slaved to do my bidding. More…

Second nature

15 February 2010 | Articles, Non-fiction

We hear a lot about how the internet is going to transform the reading and the marketing of books. But what about the act of writing? Teemu Manninen reports from the frontline of a new generation of authors for whom life has always been digital

We hear a lot about how the internet is going to transform the reading and the marketing of books. But what about the act of writing? Teemu Manninen reports from the frontline of a new generation of authors for whom life has always been digital

When we think of the future of publishing in these times of electronic reading devices, audiobooks, and the internet, when it seems as if the whole material being of literature is about to be transformed, we may ask how the marketing of books will change.

What happens when publishing goes online? How will authors cope with the new culture of the internet? More…

Our favourite things

29 January 2010 | Letter from the Editors

Every reader has his or her favourite book. It is possible to define, with acceptable criteria, when a work of fiction is ‘a good novel’: do the plot, characterisation and language work, does it have anything to say? But when is a ‘good’ novel better than another ‘good’ novel? More…

About us

8 January 2009 |

The Books from Finland online journal ceased operation on 1 July 2015, and no new articles will be published on the site.

A comprehensive online archive is available for readers to access. Brief extracts from Books from Finland may be quoted, provided that the source is cited.

If you wish to use longer extracts, please contact .

Books from Finland, an independent English-language literary journal, was aimed at readers interested in Finnish literature and culture. Its online archive constitutes a wide-ranging collection of Finnish writing in English: over 550 short pieces and extracts from longer works by Finnish authors were published from 1967 onwards.

Books from Finland featured classics as well as new writing, fiction and non-fiction, and other materials aimed at giving readers additional information on Finnish society and the wellsprings of Finnish literature. The target audience encompasses literary and publishing professionals, editors, journalists, translators, researchers, students, universities, Finns living abroad and everyone else with an interest in Finland and its literature.

Of course, publishing Finnish and Finland-Swedish literature in English requires skilled translators. Books from Finland’s editorial policy was always to use native English-speaking translators. In recent years David Hackston, Hildi Hawkins, Emily & Fleur Jeremiah, David McDuff, Lola Rogers, Neil Smith, Jill Timbers, Ruth Urbom and Owen Witesman translated for us.

Books from Finland was founded in 1967 and appeared in print format up to the end of 2008. From 2009 to 2015 it was an online publication. The journal’s archives have been fully digitised, and remaining issues will be made available in late 2015.

The Finnish Book Publishers’ Association (Suomen Kustannusyhdistys, SKY) began publishing the print edition of Books from Finland in 1967 with grant support from the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. In 1974 the Finnish Library Association (Suomen Kirjastoseura) took over as publisher until 1976, when it was succeeded by the Helsinki University Library, which remained as the journal’s publisher for the next 26 years. In 2003 publishing duties were handed over to the Finnish Literature Society (Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, SKS) and its FILI division, which remained its home until 2015. The journal received financial assistance from the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture throughout its 48 years of existence.

The editors-in-chief of Books from Finland were Prof. Kai Laitinen (1976–1989), journalist and critic Erkka Lehtola (1990–1995), author Jyrki Kiiskinen (1996–2000), author and journalist Kristina Carlson (2002–2006), and journalist and critic Soila Lehtonen (2007–2014), who had previously been deputy editor. The journal was designed by artist and graphic designer Erik Bruun from 1976 to 1989 and thereafter by a series of graphic designers: Ilkka Kärkkäinen (1990–1997), Jorma Hinkka (1998–2006) and Timo Numminen (2007–2008).

In 1976 Marja-Leena Rautalin, the director of the Finnish Literature Information Centre (now known as FILI), became deputy editor of Books from Finland. She was succeeded by Anna Kuismin (neé Makkonen), a literary scholar. Soila Lehtonen served as deputy editor from 1983 to 2006. Hildi Hawkins, who had been translating texts for the journal since the early 1980s, held the post of London editor from 1992 until 2015.

The editorial board of Books from Finland was chaired from 1976 to 2002 by chief librarian Esko Häkli, from 2004 to 2005 by the Secretaries-General the Finnish Literature Society, Jussi Nuorteva and Tuomas M.S. Lehtonen, and from 2006 to 2015 by Iris Schwanck, director of FILI. Members of the board included literary scholars, journalists, authors and publishers.

This history of Books from Finland was compiled by Soila Lehtonen, who served as the journal’s deputy editor from 1983 to 2006 and editor-in-chief from 2007 to 2014. English translation by Ruth Urbom.

Pekka Tarkka: Joel Lehtonen 1. Vuodet 1881–1917 [Joel Lehtonen 1. The years 1881–1917]

13 August 2009 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Joel Lehtonen 1. Vuodet 1881–1917

Joel Lehtonen 1. Vuodet 1881–1917

[Joel Lehtonen 1. The years 1881–1917]

Helsinki: Otava, 2009. 431 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-23229-2

€ 37, hardback

The early years of the author Joel Lehtonen (1881–1934) were harsh ones: he was the illegitimate child of a mentally disturbed mother who abandonded her six-month-year baby in the forest. Fortunately Joel was adopted by a cultured clergyman who supported his education, making it possible for him to find a career in journalism and writing. The author and critic Pekka Tarkka published his doctoral dissertation on the changes in Joel Lehtonen’s view of human character in 1977. In this new book, the first general account of Lehtonen’s life and work, he presents an interesting view of the writer’s contradictory personality. Lehtonen’s travels in France, Italy and Switzerland strengthened his knowledge of foreign languages and his interest in Romance culture essential to his translator’s work. Lehtonen’s novels and short stories are often set in his home province of Savo, which he depicted through many phases of its social development. His most popular novel, Putkinotko, was published in 1919–1920. The first volume of Tarkka’s biography ends with Lehtonen’s writing in 1917 of the novel Kerran kesällä (‘Once in summer’), about a composer returning to Finland from abroad just as the Finnish Civil War is about to begin.