Search results for "2011/04/2010/05/2009/10/writing-and-power"

A view to a kill

31 December 1997 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Klassikko (‘The classic’, WSOY, 1997). Pete drives an old Toyota Corolla without a thought for the small animals that meet their death under its wheels – or anything else, for that matter. Hotakainen describes the inner life of this environmental hazard with accuracy and precision

Pete sat in his Toyota Corolla destroying the environment. He was not aware of this, but the lifestyle he represented endangered all living things. The car’s exhaust fumes spread into the surroundings, its aged engine sweated oil onto the pavement, and malodorous opinions withered the willowherbs by the roadside. Granted that Pete was an environmental hazard, one must nevertheless ask oneself: how many people does one like him provide with employment? He leaves behind him a trail of despondent girlfriends who require the services of human relations workers, popular songwriters, and social service officials; during his lifetime, he spends tens of thousands of marks in automotive shops and service stations, on spare parts and small cups of coffee; he benefits the food industry by being a carefree purchaser of TV dinners and soft drinks. Pete is the perfect consumer, an apolitical idiot who votes with his wallet, the favorite of every government, even though no one seems interested in putting him to work, least of all himself. Every government, regardless of political power struggles, encourages its people to consume. Pete needs no encouragement, he consumes unconsciously, and one might ask: is there anything that he does consciously, the Greens and left-wingers would like him to? Does Pete make smart long-range decisions? Hardly.

Tritonus

30 September 1976 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Pentti Saaritsa playing chess. Photo by Otso Kantokorpi, 2006.

Pentti Saaritsa (born 1941), author of six collections of poetry, is one of Finland’s leading left-wing poets, who writes about a wide range of individual and social themes. An outstanding translator, he has had a major role in making Latin American literature, especially the work of Miguel Angel Asturias and Pablo Neruda, known and admired in Finland. He also translates from Russian. The first five poems below have been taken from his latest collection Tritonus (‘Tritone’, Kirjayhtymä 1976), and the last two from his Syksyn runot (‘Autumn poems’, Kirjayhtymä 1973). His poems have appeared in various anthologies abroad and are now being translated into Swedish, English and French. Pentti Saaritsa is a member of the editiorial board of Books from Finland.

![]()

1

From the bowels of each apartment house

always that one unknown sound is borne.

Sometimes like drily dripping water, sometimes

as a stone might bite a lump out of itself,

Or a child awake in the dark might learn the word hair.

And a tenant listens, makes a note of it

perhaps to punctuate the interrupted writing of his consciousness

when it makes him restless:

What now, again so soon, is it coming from me

or from the dead building.

An alarm-bell. Did anyone else hear? More…

Forest and fell

8 May 2013 | Reviews

From North to South: young Heikki Soriola on his way to represent Utsjoki in Helsinki, in 1912. Photo from Saamelaiset suomalaiset

Veli-Pekka Lehtola

Saamelaiset suomalaiset: Kohtaamisia 1896–1953

[Sámi, Finns: encounters 1896–1953]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2012. 528 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-331-9

€53, hardback

Leena Valkeapää

Luonnossa: Vuoropuhelua Nils-Aslak Valkeapään tuotannon kanssa

[In nature, a dialogue with the works of Nils-Aslak Valkeapää]

Helsinki: Maahenki, 2011. 288 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-5870-54-1

€40, hardback

The study of the Sámi people, like that of other indigenous peoples, has become considerably more diverse and deeper over recent decades. Where non-Sámi scholars, officials and clergymen once examined the Sámi according to the needs and values of the holders of power, contemporary scholarship starts out from dialogue, from an attempt to understand the interactions between different groups. More…

Breadcrumbs and elephants

27 March 2014 | Essays, On writing and not writing

In this series, Finnish authors ponder the pros and cons of their profession. Alexandra Salmela operates in two languages, her native Slovakian and Finnish, which has become her literary language. Adventure and torture alternate as she attempts to shape reality into writing

I had started to write before I knew how. With fat wax crayons, in big stick-letters, I scratched my stories in old diaries. There were lots of pictures. From the very beginning, I wrote both poetry and prose. At 11 I didn’t finish my great sea-adventure novel, but at 12 I was already writing my memoirs. They, too, somehow remained unfinished.

Writing is… I wanted to write fun, but in the end I’m not quite sure about that. Writing is adventure and liberation and terribly hard work. Torture of the imagination and the pale copying of real events. Reading is a way to escape reality and at the same time a route to the sources of reality. By writing, you can shape reality in your own image: it’s your own character fault if the result is ugly and depressing.

If I were to write a pink world, it would be so sugary that it would make everyone sick, me and other people. More…

Hearth, home – and writing

30 December 2007 | Archives online, Extracts, Non-fiction

Extracts from Fredrika Runeberg’s Min pennas saga, (‘The story of my pen’, ca. 1869–1877). Introduction by Merete Mazzarella

The joy and happiness I experience at being able to see into [her husband] Runeberg’s soul, at living with him in his heart and his thoughts, belong far too firmly to the mysteries of my soul that I should wish to attempt to express them in words. But of the life that existed around us I should like to try and give an impression of sorts.

We moved to Borgå in 1837. I was unfamiliar with the town and knew only a little old lady, weak with age, and found myself very lonely indeed, accustomed as I was to living with relatives and a genial circle of friends. I did, however, still have my two eldest sons at home to keep me happy and occupied. More…

Utopia or cacotopia?

19 August 2011 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Viljakansaari, Finland, 2008. ©Merja Salo

Do we live in the age of autopia, and if we do, what does that mean? On this earth there are now perhaps 800 million cars, all vital to our modern lifestyles. Professor and photographer Merja Salo observes landscapes through her camera with this question in mind

Extracts and photographs from Carscapes. Automaisemia (Edition Patrick Frey & Musta Taide, 2011. Translation: Laura Mänki)

The car may be the vehicle for the everyman, but not every man is a good driver. According to Hungarian- born psychoanalyst Michael Balint, good drivers have the psychological structure of philobats. With their sense of sight, they perceive space well and control it by steering their vehicle skilfully. Ocnophiles, on the other hand, are more at home as passengers. They structure the world through intimacy and touch. When driving, they cling anxiously to the steering wheel and do not perceive the continously changing situations in traffic.

Make or break?

17 November 2011 | This 'n' that

Two tax collectors: anonymous painter, after Marinus van Reymerswaele (ca. 1575–1600). Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy. Wikimedia

In Finland, tax returns are public information. So, every November the media publish lists of the top earners in Finland, dividing them into the categories of earned and investment income. Every November it is revealed who are millionaires and who are just plain rich.

The Taloussanomat (‘The economic news’) newspaper offers a list (Finnish only) of the 5,000 people who earned most last year (in terms of both earned and investment income, together with the proportion of income they have paid in tax). You can also search lists of various status and professions: rock/pop stars, media, sports, MPs, celebrities, politicians of various political parties…

So let’s take a look at Taloussanomat’s selected list of authors: number one is the celebrity author Jari Tervo (309,971 euros, tax percentage 45); number two, the internationally famous Sofi Oksanen (302,634 euros, 46 per cent); the next two are Sinikka Nopola, writer of children’s books, (264,000) and Arto Paasilinna (262,300; now after an illness, retired as a writer), translated into more than 30 languages since the 1970s. (The film critic and author Peter von Bagh made almost 900,000 euros – not by writing books, but by selling his share of a music company to an international enterprise.)

As tax data are public in Finland, there’s vigorous and decidedly informed public debate on how much money, for example, directors of public pension institutions and government offices or ministers and other top politicians are paid, and how much they should be paid: what is equitable, what is reasonable? A million dollar question indeed…

Among the European Union countries, it is only in Finland, Sweden and Denmark that there is no universal minimum wage. Here, wages are determined in trade wage negotiations. The average monthly salary in the private sector in 2010 was approximately 3,200 euros. In contrast to that, Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo, the Nokia CEO and President, who tops the 2010 tax list, earned a salary of 8 million last year, because – and precisely because – he was sacked (and replaced by the Irishman Steven Elop).

The CIA’s Gini index measures the degree of inequality in the distribution of family income in a country. The more unequal a country’s income distribution, the higher is its Gini index. The country with the highest number is Sweden, 23; the lowest, South Africa, 65 (data from both, 2005). Finland’s figure is 26.8 (2008), Germany 27 (2006), the European Union’s 34. The United Kingdom stands at 34 (2005), and the USA at 45 (2007). The figure in Finland seems to be on the rise though, as the figure back in 1991 was 25.6.

There’s been plenty of research and debate on economic inequality and the ways it harms societies. This link takes you to a fascinating video lecture (July 2011 – now seen by almost half a million people) by Richard Wilkinson, British author, Profefssor Emeritus of social epidemiology.

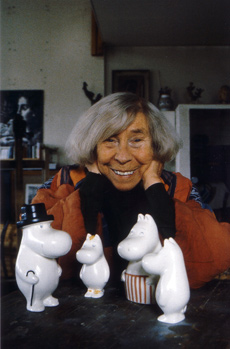

Hip hip hurray, Moomins!

22 October 2010 | This 'n' that

Partying in Moomin Valley: Moomintroll (second from right) dancing through the night with the Snork Maiden (from Tove Jansson’s second Moomin book, Kometjakten, Comet in Moominland, 1946)

The Moomins, those sympathetic, rotund white creatures, and their friends in Moomin Valley celebrate their 65th birthday in 2010.

Tove Jansson published her first illustrated Moomin book, Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (‘The little trolls and the big flood’) in 1945. In the 1950s the inhabitants of Moomin Valley became increasingly popular both in Finland and abroad, and translations began to appear – as did the first Moomin merchandise in the shops.

Jansson later confessed that she eventually had begun to hate her troll – but luckily she managed to revise her writing, and the Moomin books became more serious and philosophical, yet retaining their delicious humour and mild anarchism. The last of the nine storybooks, Moominvalley in November, appeared in 1970, after which Jansson wrote novels and short stories for adults.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) was a painter, caricaturist, comic strip artist, illustrator and author of books for both children and adults. Her Moomin comic strips were published in the daily paper the London Evening News between 1954 and 1974; from 1960 onwards the strips were written and illustrated by Tove’s brother Lars Jansson (1926–2000).

Tove’s niece, Sophia Jansson (born 1962) now runs Moomin Characters Ltd as its artistic director and majority shareholder. (The company’s latest turnover was 3,6 million euros).

For the ever-growing fandom of Jansson there is a delightful biography of Tove (click ‘English’) and her family on the site, complete with pictures, video clips and texts.

The world now knows Moomins; the books have been translated into 40 languages. The London Children’s Film Festival in October 2010 featured the film Moomins and the Comet Chase in 3D, with a soundtrack by the Icelandic artist Björk. An exhibition celebrating 65 years of the Moomins (from 23 October to 15 January 2011) at the Bury Art Gallery in Greater Manchester presented Jansson’s illustrations of Moominvalley and its inhabitants.

In association with several commercial partners in the Nordic countries Moomin Characters launched a year-long campaign collecting funds to be donated to the World Wildlife Foundation for the protection of the Baltic Sea. Tove Jansson lived by the Baltic all her life – she spent most of her summers on a small barren island called Klovharu – and the sea featured strongly in her books for both children and adults.

Power or weakness?

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

An extract from the play Hypnoosi (‘Hypnosis’, 1986). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

As you all know, this company has been my life’s work and it stands for everything I’ve had to renounce. You know that for years I have not received a penny for my personal expenses, that I am on the firm’s lowest wage level, zero.

I haven’t even had a free cup of coffee; if, because I have been working hard or I wanted to improve my concentration, I have felt like a cup of coffee, I have always gone to the canteen during my coffee break and challenged one of the boys to a bout of arm wrestling under the agreement that the loser buys the coffees, and the bloke has paid. The money never came out of the firm’s running expenses, investments, trusts or funds. More…

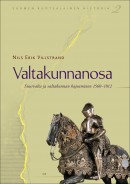

Nils Erik Villstrand: Valtakunnanosa. Suurvalta ja valtakunnan hajoaminen 1560–1812 [The constituent state. Great power and disintegration 1560–1812]

26 April 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Valtakunnanosa. Suurvalta ja valtakunnan hajoaminen 1560–1812. Suomen ruotsalainen historia 2

Valtakunnanosa. Suurvalta ja valtakunnan hajoaminen 1560–1812. Suomen ruotsalainen historia 2

[The constituent state. Great power and disintegration 1560–1812. Finland’s Swedish history 2]

[Swedish-language original: Riksdelen. Stormakt och rikssprängning 1560–1812, 2008]

Suom. [Finnish translation by] Jussi T. Lappalainen, Hannes Virrankoski

Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2012. 424 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-583-256-6

€40,hardback

This book is the second volume in a four-part series on the Swedish history of Finland. Finland was part of Sweden until 1809, when as a result of war between Sweden and Russia it came under the control of the latter; the change of governance was more or less ratified in a meeting of the Swedish Crown Prince and the Russian Tsar at Turku in 1812. Finland was reunited with its eastern region of ‘Old Finland’, which had long been a part of Russia. In his fascinating book Villstrand examines the Swedish period from several angles, using the viewpoints both of the elite and of the common people. He also reviews the conceptions of the scholars of the time, and portrays the life of the administrative and ecclesiastical circles. A special chapter is devoted to the ‘Finnish period’ of 1721–1809, when Finland gained a particular importance because of the growing threat from Russia. Finland was in many respects an equal part of Sweden, and when the country was ceded to Russia as a Grand Duchy, its old administrative and social systems were largely preserved intact. Swedish also survived for a long time, especially as the language of culture. The book’s apt illustrations are a splendid adjunct to its content.

Translated by David McDuff

So close to me

19 August 2010 | Reviews

Please try this first, before we enter the chamber of horrors. It’s a poem by Timo Harju:

… The old people’s home is the strange hand of God with which he strokes

his thinning hair,

a sudden shower of cackling in the dry linen closet, slightly

sad and lonely

God looks out, stirring his cup of tea as if it were on fire.

If Jesus had lived to grow old and gone into an old people’s home,

he would have been like these.

Timo Harju was awarded the 2009 Kritiikin kannukset prize (‘the spurs of criticism’, 2009) of the Finnish Critics' Association, SARV. Photo: Pia Pettersson

This spring a young Finnish female nurse was sentenced to life imprisonment for using insulin to murder a 79-year-old mentally retarded patient. Not long after, sentence was passed on another nurse – this time a meek and submissive-looking middle-aged woman who had murdered a whole series of elderly patients with overdoses of medication.

These are the terms – those of ordinary crime journalism – in which our recent public discussion of long-stay care of the elderly here in Finland was conducted. The discussion was followed by the usual misery of cuts, unchanged diapers, dehydration, over-medication, poor wages for hard work… No wonder that the concept of ‘healthcare wills’ and ‘living wills’, in which people are supposed to say how they want to be cared for in the last stage of their lives – is acquiring a disturbing undertone of ‘better jump before you’re pushed.’ More…