Search results for "2011/04/2010/05/song-without-words"

Big-city blues

30 September 2005 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Beige. Eroottinen kesä Helsingissä (‘Beige. An erotic summer in Helsinki’, Sammakko, 2005). Introduction by Tuva Korsström

Helsinki starts – where? Where a country girl will wear white corduroy pants if she’s eight and her pen pal tells her to. Where you’re allowed to jump in at the public swimming pool, and water splashes in your face no matter what you do, and it’s a long way to the bottom, you can’t touch. Unreal. That’s what Helsinki was like. Buildings that you recognized from pictures. A city where pictures were the starting point of your life, not experience. You step into the picture and begin your life. The step takes a long time. An entire youth. The first few days go well. You’re a tourist. The crowd of anonymous, noisy people is relaxed, you feel uninhibited. Nobody pays any attention to you. Then you start to want to feel. To talk. To say hi to somebody. The waiting begins, and there’s nothing you can do to speed it up. You have to live in the city. Ten years and you’re in, maybe, a little. Be there. Stay. You’ll circulate around the triangle formed by Sokos, Stockmann, and Forum department stores. They’re familiar from pictures, you’re wary of the others. The streetcar home. Home and downtown. The city. The lanes. Conduits. Lights. Trams. Taxis. Buses. The first negro. The first stop at a traffic light. The yellow stone building. The colorful cottages at the foot of the bridge. More…

1968

30 March 2005 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Lugna favoriter (‘Quiet favourites’, Söderströms, 2004)

We were in the space age, the age that came and went, the age of space and great dreams, when space was what we talked about and space was what the papers wrote about, and about Vietnam and protests and revolution, in articles precocious and prematurely old children spelled their way through, children living in the mixed forests of the North which had recently been transformed into gleaming suburbs where ink-caps, puffballs and parasol mushrooms still grow in the backyards of high-rise tower blocks. It says in the paper that we humans will soon have to move away, leave the Earth because our planet has become overcrowded and almost uninhabitable, and space and the eternity of space are waiting for us and we have engineers of the highest class who will soon solve such small problems as still remain. It’s not a question of forests of mixed trees or ink-caps or parasol mushrooms or other earthly things, it’s a question of it being too late now, that we must go further, first to the moon and then to Mars and Andromeda and further still, and here are some of the key words and phrases: space programme, space race, Apollo, Vostok, Tereshkova and Glenn. For humanity has dreams, dark mixed visions and a nagging and not easily extinguished sense of life’s inscrutability and greatness, but down here all goes on as before, we kill each other, we kill our fellow men in jungles and marshes, we kill them amid rugged mountains and in snow-clad forests, we poison them and blow them to pieces, we kill them in dark backstreets and in ramshackle wooden hovels and in mighty marble palaces where the bath-taps glitter with gold. Only a chosen few are able to escape, and to do this they have to set off upwards into a coolness, and seek out a darkness and solitude where there will be no anxiety or feelings of guilt. But before they can get there they must face opposition of a magnitude that can only be overcome by a fierce rush of power, and before the rocket can start it sits and breathes out smoke and gases and fire for a good thirty seconds before lifting off slowly and reluctantly as if unwilling to leave its home planet, as if it hasn’t the slightest desire to go, but when it gets under way it travels at incomprehensible speeds over unimaginable distances, it’s only 108 years since Lenoir invented the internal combustion engine and we are already up in space where it’s silent and cool and peaceful, just a little anxiety in case some instrument fails, in case some double safeguard shows itself insufficient, otherwise nothing, just weightlessness and silence, just the oceans and deserts and mountain-chains on the surface of our blue globe. Though let’s be fair: the Chinese, who haven’t been up in space, claim that the Great Wall of China must be visible from up there, but on the other hand they have nothing to say about the visibility of new-built suburbs in the miserable little capitals of small underpopulated countries with frosty climates. More…

The height of the night

15 October 2009 | Letter from the Editors

The autumnal equinox is past; and as we tilt towards the winter solstice, here in these northerly latitudes, the darkness expands palpably from day to day, giving more space for introspection – high on the list of Finnish national pastimes – and for reading.

The autumnal equinox is past; and as we tilt towards the winter solstice, here in these northerly latitudes, the darkness expands palpably from day to day, giving more space for introspection – high on the list of Finnish national pastimes – and for reading.

We want to make our website primarily a place for reading – not, in other words, for clicking, going on to the next thing. To think to the end what cannot be thought to the end elsewhere, as the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam said of his experience of staying in what was, at the turn of the 20th century, still Finnish Karelia. So you will not find our texts littered with links; for the most part, links appear at the end of a piece, not in it. More…

The Session

30 June 1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Pappas flicka (‘Daddy’s girl’, 1982), an extract of which appears below, is published in Finland by Söderstrom & C:o and in Sweden by Norstedt. The Finnish translation is published by Tammi. Introduction by Gustaf Widén

At first I say nothing, as usual.

Dr Berg also sits in silence. I can hear him moving in his chair and try to work out what he’s doing. Is he getting out pen and paper? Or perhaps he has a tiny soundless tape-recorder he is switching on.

Or is he just settling down, deep down into his armchair, one leg crossed over the other, like Dad used to sit? I used to climb up on to his foot. The he would hold my hands and bounce his foot up and down, and you had to say “whoopsie” and finally with a powerful kick, he would fling me in the air so that I landed in his arms.

I have worked it out that the little cushion under my head is to stop us lunatics from turning our heads round to look at Herr Doktor.

It would certainly be nice to sit bouncing up and down on Dr Berg’s foot. His ankle would rub me between my legs …

I soon start feeling ashamed and blush.

“Mm,” says Dr Berg, as if reading my thoughts. Or can he see my face from where he is sitting? I try rolling my eyes up to catch a glimpse of him, but all I can see is the ceiling with all its thick beams.

“I seem to have been here before,” I say. More…

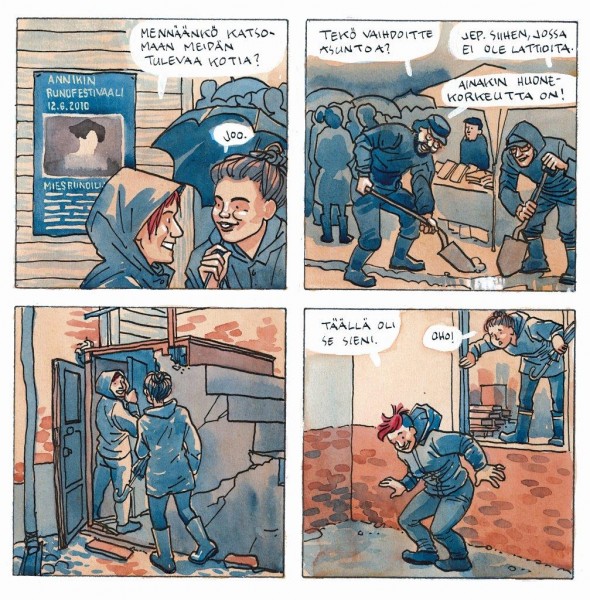

Picture this

9 April 2015 | Articles

It’s impossible to put Finnish graphic novels into one bottle and glue a clear label on to the outside, writes Heikki Jokinen. Finnish graphic novels are too varied in both graphics and narrative – what unites them is their individuality. Here is a selection of the Finnish graphic novels published in 2014

Graphic novels are a combination of image and word in which both carry the story. Their importance can vary very freely. Sometimes the narrative may progress through the force of words alone, sometimes through pictures. The image can be used in very different ways, and that is exactly what Finnish artists do.

In many countries graphic novels share some common style or mainstream in which artists aim to place themselves. In recent years an autobiographical approach has been popular all over the worlds in graphic novels as well as many other art forms. This may sometimes have led to a narrowing of content as the perspective concentrates on one person’s experience. Often the visual form has been felt to be less important, and clearly subservient to the text. This, in turn, has sometimes even led to deliberately clumsy graphic expression.

This is not the case in Finland: graphic diversity lies at the heart of Finnish graphic novels. Appreciation of a fluent line and competent drawing is high. The content of the work embraces everything possible between earth and sky.

Finnish graphic novels are indeed surprisingly well-known and respected internationally precisely for the diversity of their content and their visual mastery.

Life on the block

Cause of death

30 June 1999 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Åtta kroppar (‘Eight bodies’, Söderströms, 1998). Introduction by Ann-Christine Snickars

It was a bailer, a blue one. There they were, he, she, the bailer and a stormtossed net on the stern board of a hired boat. The boat had come with the cottage and the cottage with ‘Autumn archipelago package. Now nature is aglow.’

And it was aglow.

Masses of foliage and apples, damson and shiny russula spread out around them in all their glory. It happened everywhere, that glowing. Wherever one turned one’s gaze there was something ready to be picked or ready to fall, ready in general. Those first days they had, at least to each other, she to him, feigned enthusiasm about all this ripe richness, but that time was over.

Their time of fire and flames was over. More…

Kullervo’s story

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Paavo Haavikko wrote this manuscript for the television series Rauta-aika (‘Age of iron’), broadcast in 1982. lt also appeared as a book in 1982, complemented by Kullervon tarina (‘Kullervo’s story’ ) which had been omitted from the original. The text follows the stories of the Kalevala, but they are given a new interpretation: the characters are demythologised, they resign themselves to their fates – they are like ourselves. These extracts are the final scenes in which incest, revenge and death appear in a slightly different guise from Kalevala, or Kivi’s Kullervo.

– Mother, on the road I met your daughter, who is my sister, and took her into my sleigh. She had broken one of her skis. Spring came in one day, the clouds in front of the moon tore themselves to shreds so that two moons passed in one night. Winter went, Spring came, I brought the sleigh back, and I slept on top of the sacks so that not a single grain or seed would be lost. It’s all in the sacks now, saved. The clouds tore off their clothes and washed them in the rivers of rain, and naked, in the dark, they waited for their clothes to dry, those clouds. They even darkened the moon, they would have killed it if they could have reached that far, as it spied on the cloud women who were washing the clothes they had taken off in the waters of heaven, and two moons passed in one night, Kullervo says to his mother, piling up lies like a little boy. Many words. More…

No one can tell

31 March 1999 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Ahava (WSOY, 1998)

And life went on, went on as a kind of weird fugue,

a forked path that drops across your eyes,

rejecting simple questions.

Which summer was that,

I ask in December,

in a high room, with a tiled stove, a bricked up

nostalgic sentence about the warmth of other times,

a crossing where all the world's words

discover the the comparative degree of silence,

the one with meaning.

Should I peep across a couple of cloudy stanzas to get a better view,

but again my eye conjures up a medieval constricted soul.

All that's left is a thirst of all the senses, a frigid study of sentences,

of bones.