Search results for "herbert lomas/www.booksfromfinland.fi/2004/09/no-need-to-go-anywhere"

A dictionary of human destinies

31 March 2001 | Fiction, Prose

Short stories from Av blygsel blev Adele fet (‘It was embarrasment that made Adele fat’, Söderström & Co., 2000)

Adele

It was embarrassment that made Adele fat. It wasn’t from hunger that her fridge-fumbling fingers began to grow nimble, but from confusion. And it was never knowing what her tongue ought to say that led her to the concrete business of the fridge. Her tongue certainly knew all about tasting. It could feel her teeth chewing even if it didn’t know how to speak. It became a better and better judge of brussels sprouts and speckled sausage. The rest was just good morning and thanks, thanks and goodbye and nice day. More…

Northern exposure

3 September 2005 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Valon reunalla (‘At the edge of light’, Teos, 2005). Introduction by Kristina Carlson

Kari

The village despised all those who left. They hated us too, though we were still only planning our final escape.

We used to escape the village. We would hide from its gaze in the forest or the cemetery where the gravestones were so close together that there was no room for the trees to grow. We knew why the freight train brought the village so many dead and so few living. It was the village’s fault. It had a wicked soul. The grown-ups didn’t know it. We knew it, but no one asked us. Death was within us; it was alive. Asking would have been too dangerous….

On the backs of the headstones we carved our own marks with the end of a knife. We blew out the candles laid at the graves of suicide victims. We worshipped them in the dark and no new candles were ever brought to their graves. The parents of those who died so young drove south. They were looking for stations with real waiting rooms and staff that made announcements. They sat on the hard benches waiting, waiting for the trains to come, at the right time; hoping the years wouldn’t wreak havoc after all, hoping they’d roll slowly back along the tracks, to brighten as they approached the village, giving life once again to their children. And everything could start over. More…

Childhood revisited

31 March 2006 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Tämän maailman tärkeimmät asiat (‘The most important things of this world’, Tammi, 2005). Introduction by Jarmo Papinniemi

I was supposed to meet my mother at a café by the sea. She would be dressed in the same jacket that I had picked out for her five years ago. She would have on a high-crowned hat, but I wasn’t sure about the shoes. She loved shoes and she always had new ones when she came to visit. She liked leather ankle boots. She might be wearing some when she stepped off the train, looking out for puddles. She didn’t wear much make-up. I don’t remember her ever using powder, although I’m sure she did. I could describe her eye make-up more precisely: a little eye shadow, a little mascara, and that’s all.

That’s all? I don’t know my mother. As a child, I lived too much in my own world and it was only after I left home that I was able to look at her from far enough away to learn to know her. She had been so near that I hadn’t noticed her. More…

Close encounters

31 March 2003 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Stories from Konservatorns blick (‘A conservator’s gaze’, Schildts, 2002). Introduction by Fredrik Hertzberg

Unmarried and randy in a hotel foyer

The hotel foyer in Baghdad was swarming with people as anxious to advertise themselves as westerners at the opening of an art exhibition. I bumped into a man who quickly introduced himself, handed me his card and wondered whether I had an engagement that evening.

‘No,’ I said, truthfully.

‘Then kindly come home with me at nine,’ he said, with a florid gesture in the direction of my breasts.

‘No thank you,’ I answered. ‘I do have an engagement, I’ve just remembered.’ More…

Hotel for the living

30 June 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Hotelli eläville (‘Hotel for the living’, 1983). Introduction by Markku Huotari

Raisa and Pertti are a married couple with three children, Katrielina, Aripertti and Artomikko. When she discovers she is to have another, whom she names Katjaraisa, Raisa decides to have an abortion, because another child, even if welcome, would now jeopardise her career – she has been offered a job with an international company at the very top of the advertising world. Raisa is the successful entrepreneur of the novel – on the one hand coldly calculating, without feeling, on the other superficially sentimental, perhaps the most startlingly ironic of the characters in Jalonen’s novel. His image of the brave new woman?

During her lunch hour Raisa took a walk via the laboratory, asked reception for the envelope and thrust it unregarded into her handbag. She was aware of her already knowing, but short of the envelope, there would as yet be no restrictions, nor were there any decisions that would have to be made. She had called Tom Eriksson, discussed yet again the same points and particulars, and ended tracing a finger over the two beautiful pictures on her wall. ‘The loveliest of seas has yet to be sailed’ and ‘I am life! For Life’s sake.’

She thought of Katjaraisa, her features, the palms the breadth of two fingers, just as Katrielina’s had been, and the same button-eyed gazing look as Katrielina. More…

Canberra, can you hear me?

31 March 1987 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Johan Bargum. Photo: Irmeli Jung

A short story from Husdjur (‘Pets’, 1986)

Lena called again Sunday morning. I had just gotten up and was annoyed that as usual Hannele hadn’t gone home but was still lying in my bed snoring like a pig. The connection was good, but there was a curious little echo, as if I could hear not only Lena’s voice but also my own in the receiver.

The first thing she said was, ‘How is Hamlet doing?’

She’d started speaking in that affected way even before they’d moved, as if to show us that she’d seen completely through us.

‘Fine,’ I said. ‘How are you?’

‘What is he doing?’

‘Nothing special.’

‘Oh.’

Then she was quiet. She didn’t say anything for a long while.

‘Lena? Hello? Are you there?’

No answer. Suddenly I couldn’t stand it any longer. More…

Garden graft

2 September 2010 | Essays, Non-fiction

A chapter from Vapaasti versoo. Rönsyjä puutarhasta (‘Freely sprouting. Runners from the garden’, Kirjapaja, 2010)

If you sit in your garden and feel a bit like you’re tucked uncomfortably at the end of the dock in a guest berth, the reason is this: the garden hasn’t yet found a place in your muscle memory. Because it is only at the point when the garden has settled into your muscle memory, into your senses in as many ways as possible, that it will feel like your own. And that, of course, takes working in the garden, not just sitting in it.

So you should know your rose – not just its lovely smell but also the memory that you get from the shovel handle of when you planted it, or even the memory of the prick of its thorn on your finger. You can anchor every little detail in your senses, and it doesn’t even take much imagination. The scent of thyme on your fingertips, the downy fluff of a pasque flower against your palm, the silken glow of a peony opening in the morning sunlight – or the sumptuous mist of the wee hours of a summer morning twining over everything, and the rare experience of wading through it. More…

Telling the tale

30 June 2007 | Archives online, Essays, On writing and not writing

Half of the art of writing lies in not telling the reader everything, writes Kaari Utrio, historian and writer of historical fiction

Fantasy is a curse to science but the lifeblood of literature. The combination of these two opposing factors lies at the core of my work. In the expression, ‘historical novel’, the emphasis is on the word ‘novel’. To me a novel is a story, and I am a storyteller. This is an important basic definition for the genre of literature I write. More…

Letter to the wind

30 September 2002 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Haapaperhonen (‘The butterfly’, Gummerus, 2002). Introduction by Kristina Carlson

When Father comes to visit me, he sometimes sings a hymn. I can’t ask him not to. But when he doesn’t, I wonder why not, whether there’s something up with him. I can’t ask him to sing, but something is missing, the same thing that there seems to be too much of when he sings. It’s too much, but I miss it when it’s not there. I wonder about it after Father’s gone; my thoughts curl into dreams and I sleep.

When I sleep I don’t know I’m here, in a strange place. I’m at home, sleeping at home, in my own bed. The window is the right size, not too big like it is here; here there isn’t really a window at all, half the wall is missing and instead there’s glass. Behind a glass wall it’s not safe, everything is taken through it, including me. But sleep takes me to safety; I’m at home there. I breathe it peacefully. In the cabin there are two breathings, mine and Turo’s, and in the bedroom Father’s breathing. They are in no hurry to drive time away; time can linger, sleep, the moment of night, and when sleep withdraws there is no hurry either; I can sit in peace on the window seat and gaze at the cloudy, moonlit yard. The apple tree is asleep; it’s the only one. The fieldfares ate the apples before we could pick them, but it did not bother me or Father. It was good to look at the flock of fieldfares making a meal of the apple tree. Then they went away. More…

Trial and error?

31 December 2008 | Archives online, Essays, On writing and not writing

If you want to write, you need to do it every day, says the author Monika Fagerholm. Trial and error are necessary for her – and so is not being afraid of getting lost in the woods in the process, because only then can amazing things be found

Writers write and writers write every day. I remember seeing this in one of those inspirational guides on writing I enjoy reading – even if they don’t necessarily help you in pursuing your daily writing as much as you would hope. At the worst, they give you a kind of exhausting energy which just leaves you drained. And yes, turning to these kinds of manuals almost always involves an element of desperation; you don’t need advice when everything is going great. More…

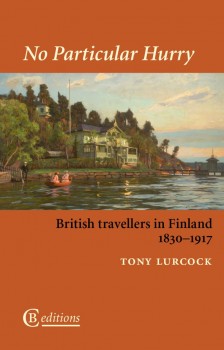

No sex in Finland

31 July 2013 | Reviews

Tony Lurcock

Tony Lurcock

No Particular Hurry. British Travellers in Finland 1830–1917

London: CB editions, 2013. 278 p.

ISBN 978-0-9567359-9-7

£10, paperback

For British travellers of the late 18th- and early 19th-century Finland was mainly a transit area between Stockholm and St Petersburg, or on the way to exotic Lapland. A century later, the country was already a tourist destination in itself, a newly emergent nation state, though still subordinate to Russia.

Tony Lurcock’s anthology of travel literature about Finland is a sequel to his collection ‘Not so Barren or Uncultivated’: British Travellers in Finland 1760–1830 (reviewed in Books from Finland in June 2013).

The practical conditions of tourism were changing. English-language tour guides were being published, and Britain now had direct steamship connections to Finland, where rail, road and inland waterway traffic had been established. In 1887 the Finnish Tourist Association was founded with the aim of making life easier for foreign tourists on selected travel routes. However, the British – like many other foreigners – marvelled at some of the country’s curious features: the excruciating rural journeys by horse and cart, the wretched inns and strange choice of food, the rye bread and milk-drinking, and of course the sauna. But to this there were also exceptions, in the form of new, surprisingly resplendent hotels, world-class dinners and the life of the modern city. More…

Howl came upon Mr Boo

31 December 1983 | Archives online, Children's books, Drama, Fiction

The first Mr Boo book was published in 1973. Mr Boo has also made his appearance on stage this year; his theatrical companions are the children Mike and Jenny, who are not easily frightened – Mr Boo’s courage is a different matter, as can be seen in the extract from the stage play that follows overleaf.

Hannu Mäkelä describes the birth of Mr Boo:

To be honest, Mr Boo has long been my other self. The first time I drew a character who looked like him, without naming it Boo, I was really thinking of my fifteen year-old self.

The years went by and the Mr Boo drawing was forgotten for a time. It hadn’t occurred to me to write for children; I seemed to have enough to do coping with myself. Then I met Mr Boo, whom I had not yet linked up with my old drawing. My son was about six years old and we had been invited out. There were several children present. As I recall it it was a wet Sunday afternoon. I had entrenched myself with the other grown-ups in the kitchen to drink beer. The noise of the children grew worse and worse (in other words they were enjoying themselves). At last the women could bear it no longer and demanded that I, too, get to work. Really, what right had I always to be sprawled at a table with a beer glass in my hand? None. So I rose and went into the sitting-room. I shouted at the children to form a circle around me. At that time I had a motto: ‘Mäkelä – friend to children and dogs’. The reverse was true of course. The name Mr Boo occurred to me, probably as a result of some obscure private (and possibly even erotic) pun and I begun to tell a story about him. In telling it I paused dramatically and accelerated just as primary school teachers are taught to do: that part of my training, after all, wasn’t wasted. I was astonished; the children listened in complete silence. And if my memory doesn’t fail me (or even if it does, this is the way I wish to remember it), at the end of the story the smallest of the children said, rolling his r’s awkwardly, ‘Hurrrrah’. I was hooked.

The children themselves asked me to tell the same stories again. They still enjoyed them. It wasn’t long before I began to think seriously of writing a whole book about Mr Boo. For the first time in my life I really wanted to write for children. Every day after work I wrote a new Mr Boo story. Then in the evening I read it to my son. That is how the stories grew into a book.

The child likes right to triumph; he likes the good and the moral. The child is the kind of person we adults try in vain to be. It was only through Mr Boo that I began to see children in a totally new way and above all to become seriously interested in them.