Search results for "jarkko/2011/04/2010/05/2009/10/writing-and-power"

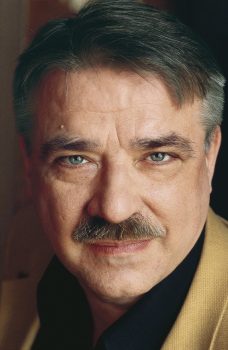

John Simon: Koneen ruhtinas. Pekka Herlinin elämä [The Prince of Kone. The life of Pekka Herlin]

15 January 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Koneen ruhtinas. Pekka Herlinin elämä

Koneen ruhtinas. Pekka Herlinin elämä

[The Prince of Kone. The life of Pekka Herlin]

Finnish translation of original English manuscript completed by various translators in collaboration with the author

Helsinki: Otava, 2009. 415 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-23478-4

€ 33, hardback

Pekka Herlin (1932–2003) was the long-serving chairman of the board of the Kone lift and escalator company. During Herlin’s tenure, Kone completed a number of corporate acquisitions to become a major global corporation. John Simon, an American writer and researcher, takes an unusually honest and direct approach; the project was undertaken at the request of Antti Herlin, the current chairman of the board at Kone and son of Pekka Herlin. Pekka Herlin was known for being both gregarious and a cool-headed business strategist, but his irascible, unorthodox nature was familiar to many as well. Within his family he emerged as a tyrannical alcoholic with a severely disturbed personality, feared by his children. John Simon interviewed a great many people who knew Pekka Herlin personally, including members of Herlin’s immediate family. This biography was Finland’s best-selling non-fiction book in the autumn of 2009.

Tapio Markkanen Paratiisista katsoen. Tähtitaivaan karttojen historiaa [Viewed from Paradise. A history of maps of the night sky]

4 June 2010 | Mini reviews

Paratiisista katsoen. Tähtitaivaan karttojen historiaa

Paratiisista katsoen. Tähtitaivaan karttojen historiaa

[Viewed from Paradise. A history of maps of the night sky]

Helsinki: Ursa (Astronomical Association), 2009. 143 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-5329-80-3

€ 32, paperback

This book presents a scientific and cultural history of mapping the night sky, from ancient times up to the present day. In addition to the technical processes involved in producing celestial maps, it touches on a broad range of cultural connections, since the practice of mapping the heavens has always been inextricably linked with economic, cultural and political concerns throughout human history. How has mankind around the world experienced and comprehended the night sky? The title of this book refers to the ancient practice of portraying the skies the wrong way round – as a mirror image, as if viewed from heaven. ‘That’s how the gods would have seen it,’ the author, Professor Tapio Markkanen, an astronomer at the University of Helsinki, reminds us. This book was published in conjunction with an exhibition organised by the National Library of Finland as part of the International Year of Astronomy in 2009. Many of the maps reproduced in this book are from the Nordenskiöld Collection, housed in the National Library, and included in the UNESCO Memory of the World programme.

Monika Fagerholm: Glitterscenen [The Glitter Scene]

17 November 2009 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Glitterscenen

Glitterscenen

[The Glitter Scene]

Helsingfors: Söderströms, 2009. 407p.

ISBN 978-951-522-467-5

€29.90

Säihkenäyttämö

Finnish translation by Liisa Ryömä

Helsinki: Teos, 2009. 455 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-127-7

€29.90, hardback

In Glitterscenen Fagerholm reveals the shabby details of the murder mystery that was the essence of her celebrated Den amerikanska flickan, The American Girl (2006). In a sense, the two books are psychological thrillers, but they are also much more than that: the American girl’s death is a myth about destruction and creation – a narrative about love, death and glamour that attracts and seduces cohort after cohort of young women in the District, a place somewhere in Finland that is in the process of being transformed from the rural to the suburban. Like no other author, Fagerholm combines the advantages of plot-based realism with the deep psychological excavation of collective dreams and the secret layers of the unconscious. In the centre of the District there is a kiosk where the local priest’s daughter, fat May-Gun, presides over dirty magazines, sickly candy and magnificent dreams. Across the square, eyed by horny small-town greasers, walks young and blonde Suzette. The result is a deadly drama, propelled by grief and narcissism. The Glitter Scene is the goal of our dreams, but also a dangerous place of instant gratification and sudden death.

Not a world language, and yet….

16 January 2015 | Articles, Non-fiction

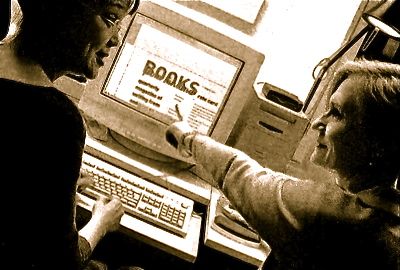

The editors (Hildi Hawkins and Soila Lehtonen) at the screen: we begun publishing material on our website in 1998. Photo: Jorma Hinkka, 2001

Longevity may not generally be a virtue of literary magazines – they tend to come and go – but Books from Finland, which began publication in 1967, has stuck around for a rather impressively long time. Literary life, as well as the means of production, has changed dramatically in the almost half-century we have been in existence. So where do we stand now? And what does the future look like?

This is the farewell letter from the current Editor-in-Chief, Soila Lehtonen – who began working for the journal in 1983

‘The literature of Finland suffers the handicap of being written in a so-called “minor” language, not a “world” language…. Finland has not entirely been omitted from the world-map of culture, but a more complete and detailed picture of our literature should be made available to those interested in it.’

Thus spake the Finnish Minister of Education, R.H. Oittinen, in early 1967, in the very first little issue of Books from Finland, then published by the Publishers’ Association of Finland, financed by the Education Ministry.

Forty-seven years, almost 10,000 printed pages (1967–2008) and (from 2009) 1,400 website posts later, we might claim that the modest publication entitled Books from Finland, has accomplished the task of creating ‘a more complete and detailed picture’ of Finnish literature for anyone interested in it. More…

In the detail?

11 December 2009 | Essays, Non-fiction

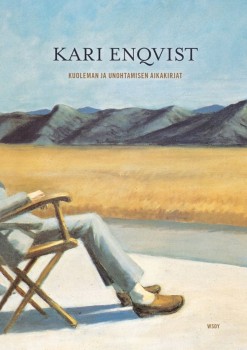

Extracts from Kuoleman ja unohtamisen aikakirjat (‘Chronicles of death and oblivion’, WSOY, 2009)

Extracts from Kuoleman ja unohtamisen aikakirjat (‘Chronicles of death and oblivion’, WSOY, 2009)

What’s the meaning of life? There are those who seek it in religion, while for others that is the last place to look. The scientist Kari Enqvist ponders why some people, including himself, seem physiologically immune to the lure of faith. Perhaps, he suggests, we should look for significance not in the big picture, but in the marvel of the fleeting moment

As a young boy I must have held religious beliefs. However, I cannot pinpoint exactly when they disappeared. At some point I eventually stopped saying my evening prayers, but I am unable to remember why or when this happened. ‘I was born in a time when the majority of young people had lost faith in God, for the same reason their elders had had it – without knowing why,’ writes the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa in The Book of Disquiet. More…

A roof with a view

27 August 2009 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mistä on mustat tytöt tehty? (‘What are black girls made of?’, Tammi, 2009) Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

I’m a chimney sweep’s daughter, born October 1962 as a gift, a light to a darkened world. I’ve had lots of mothers, but none of them ever stuck around for good. One of them gave birth to me, so she’s Mother, not mother. Her name is Dewdrop, because water has spilled over the only photograph of My Mother and now her face has dissolved into a single translucent droplet; her nose, cheeks and chin are now a fat, shiny blob that looks like it’s about to fall out of the bottom of the picture. More…

Not so weird?

12 December 2013 | Non-fiction, Reviews

Johanna Sinisalo. Photo: Katja Lösönen

Johanna Sinisalo’s new novel Auringon ydin (‘The core of the sun‘, Teos, 2013), invites readers to take part in a thought experiment: What if a few minor details in the course of history had set things on a different track?

If Finnish society were built on the same principle of sisu, or inner grit, as it is now but with an emphasis on slightly different aspects, Finland in 2017 might be a ‘eusistocracy’. This term comes from the ancient Greek and Latin roots eu (meaning ‘good’) and sistere (‘stop, stand’), and it means an extreme welfare state.

In the alternative Finland portrayed in Auringon ydin, individual freedoms have been drastically restricted in the name of the public good. Restrictions have been placed on dangerous foreign influences: no internet, no mobile phones. All mood-enhancing substances such as alcohol and nicotine have been eradicated. Only one such substance remains in the authorities’ sights: chilli, which continues to make it over the border on occasion. More…

Landscape

30 June 2006 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

(Landskap, 1919). Introduction by Juha Virkkunen

12 March

To begin with, there’s a great white field. The field is criss-crossed with low slender fences and little patches of yellow-green stubble peering up through the snow, and hare-tracks slanting away towards the stubble. But we won’t notice the fences and the stubble and the hare tracks. Because we’re going to take a wider, more sort of decorative view.

So we see the great white field. And where the field ends a dark green screen has been drawn. The screen has been cut short rather amusingly in the middle, so one can see yet another white held. This belongs to another village. And this other village itself has crept up timidly to the forest-clad hill and lies close to it, so we don’t notice this other village. Because we want to take a wider view of things. More…