Search results for "paavo haavikko"

New from the archive

26 March 2015 | This 'n' that

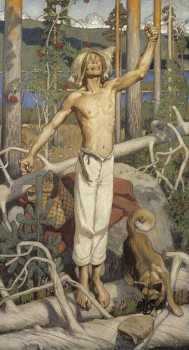

Kullervo’s curse. Painting by Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1899)

Finland’s national epic adapted for the stage by Finland’s national writer: best known as the author of the first significant novel in Finnish, Seitsemän veljestä (Seven Brothers, 1870), Aleksis Kivi (1834-1972) also turned one of the Kalevala’s grimmest stories, that of Kullervo – a tale of incest, revenge and death– into a five-act tragedy.

The translation is by one of Books from Finland’s most long-standing collaborators, David Barrett (1914-1998), a true linguistic genius with a speciality in Georgian as well as Finnish in addition to classical Greek; as well as his work with texts in Finnish and Georgian, he made extensive translations of Aristophanes for Penguin Classics. Barrett felt, as he argues here in his introduction, ‘that Kullervo, if suitably translated, might succeed where Seven Brothers had failed, in bringing Kivi’s genius to the notice of the English-speaking world’.

Was he right? It is up to you, dear readers, to judge.

For a very different, demythologized, view of the Kullervo story, we also publish a manuscript by the modernist poet Paavo Haavikko (1931-2008) from his television adaptation Rauta-aika (‘Age of iron’, 1982).

The Kalevala is in development as a film by the Finnish entertainment company Rovio, of Angry Birds game, and the Finnish-born video game company Supercell. It remains to be seen how the Kalevala take to the big screen.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues, with a total of 372 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Older and wiser?

9 October 2012 | This 'n' that

Illustration: Virpi Talvitie (from Täyttä päätä. Runoja ikääntyville, ‘Full steam ahead. Poems for ageing people’, edited by Tuula Korolainen and Riitta Tulusto)

Nobody can claim that old age is hot, or media-sexy. Yes, but what are older people really like? Are they the bingo-obsessed grannies in floral frocks or old geezers living in the past of popular opinion?

No longer. In just a few years the baby-boom generation will be entering their seventies, when ‘old age’, in its current Western definition, begins. (Until then, senior citizens are allowed to remain ‘adults’.)

Are the old people’s homes ready for them? This new elderly generation will be wanting to listen to Elvis, the Rolling Stones and the Beatles rather than the tango. More…

Kullervo’s story

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Paavo Haavikko wrote this manuscript for the television series Rauta-aika (‘Age of iron’), broadcast in 1982. lt also appeared as a book in 1982, complemented by Kullervon tarina (‘Kullervo’s story’ ) which had been omitted from the original. The text follows the stories of the Kalevala, but they are given a new interpretation: the characters are demythologised, they resign themselves to their fates – they are like ourselves. These extracts are the final scenes in which incest, revenge and death appear in a slightly different guise from Kalevala, or Kivi’s Kullervo.

– Mother, on the road I met your daughter, who is my sister, and took her into my sleigh. She had broken one of her skis. Spring came in one day, the clouds in front of the moon tore themselves to shreds so that two moons passed in one night. Winter went, Spring came, I brought the sleigh back, and I slept on top of the sacks so that not a single grain or seed would be lost. It’s all in the sacks now, saved. The clouds tore off their clothes and washed them in the rivers of rain, and naked, in the dark, they waited for their clothes to dry, those clouds. They even darkened the moon, they would have killed it if they could have reached that far, as it spied on the cloud women who were washing the clothes they had taken off in the waters of heaven, and two moons passed in one night, Kullervo says to his mother, piling up lies like a little boy. Many words. More…

In memoriam Herbert Lomas 1924–2011

23 September 2011 | In the news

Herbert Lomas. Photo: Soila Lehtonen

Herbert Lomas, English poet, literary critic and translator of Finnish literature, died on 9 September, aged 87.

Born in the Yorkshire village of Todmorden, Bertie lived for the past thirty years in the small town of Aldeburgh by the North Sea in Suffolk. (Read an interview with him in Books from Finland, November 2009.)

After serving two years in India during the war, Bertie taught English first in Greece, then in Finland, where he settled for 13 years. His translations – as well as many by his American-born wife Mary Lomas (died 1986) – were published from as early as 1976 in Books from Finland.

Bertie’s first collection of poetry (of a total of ten) appeared in 1969. His Letters in the Dark (1986) was an Observer book of the year, and he was the recipient of several literary prizes. His collected poems, A Casual Knack of Living, appeared in 2009.

In England Bertie won the Poetry Society’s 1991 biennial translation award for one of his anthologies, Contemporary Finnish Poetry. The Finnish government recognised his work in making Finnish literature better known when it made him a Knight First Class of Order of the White Rose of Finland in 1987.

To Books from Finland, he made an invaluable contribution over almost 35 years – an incredibly long time in the existence of a small literary magazine. The number of Finnish authors and poets whose work he made available in English is countless: classics, young writers, novelists, poets, dramatists.

Bertie’s speciality was ‘difficult’ poets, whose challenge lay in their use of end-rhymes, special vocabulary, rhythm or metre. He loved music, so the sounds and tones of words, their musicality, were among the things that fascinated him. Kirsi Kunnas’ hilarious, limerick-inspired children’s rhymes were among his best translations – although actually nothing in them would make the reader think that the originals might not have been written in English. A sample: There once was a crane / whose life was led / as a uniped. / It dangled its head / and from time to time said:/ It would be a pain / if I looked like a crane. (From Tiitiäisen satupuu, ‘Tittytumpkin’s fairy tree’, 1956, published in Books from Finland 1/1979.)

Bertie also translated work by Eeva-Liisa Manner, Paavo Haavikko, Mirkka Rekola, Pentti Holappa, Ilpo Tiihonen, Aaro Hellaakoski and Juhani Aho among many, many others; for example, the prolific writer Arto Paasilinna’s best-known novel, Jäniksen vuosi / The Year of the Hare, appeared in his translation in 1995. Johanna Sinisalo’s unusually (in the Finnish context) non-realist troll novel Ennen päivänlaskua ei voi / Not Before Sundown, subsequently translated into many other languages, appeared in 2003. His last translation for Books from Finland was of new poems by Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen in 2009.

It was always fun to talk with Bertie about translations, language(s), writers, books, and life in general. He himself said he was a schoolboy at heart – which is easy to believe. He was funny, witty, inventive, impulsive, sometimes impatient – and thoroughly trustworthy: he just knew how to find the precise word, tone of voice, figure of speech. He had perfect poetic pitch. As dedicated and incredibly versatile translators are really hard to find anywhere, we all realise our good fortune – both for Finnish literature and for ourselves – to have worked, and enjoyed with such enjoyment, with Bertie.

Poet Aaro Hellaakoski (1893–1956) was not a self-avowed follower of Zen, but his last poems, in particular, show surprisingly close contacts with the philosophy. ‘Secrets of existence are revealed once one ceases seeking them’, the literary scholar Tero Tähtinen wrote in an essay published alongside Bertie’s new Hellaakoski translations in (the printed) Books from Finland (2/2007). Bertie was fond of Hellaakoski, whose existential verses fascinated him; among his 2007 translations is The new song (from Vartiossa, ‘On guard’, 1941):

The new song |

Uusi laulu |

| No compulsion, not a sting. | Ei mitään pakota, ei polta. |

| My body doesn’t seem to be. | On ruumis niinkuin ei oisikaan. |

| As if a nightbird started to sing | Kuin alkais kaukovainioilta |

| its far shy carol from some tree – | yölintu arka lauluaan |

| as if from its dim chrysalis | kuin hyönteistoukka heräämässä |

| a little grub awoke to bliss – | ois kotelossaan himmeässä |

| or someone struck from off his shoulder | kuin hartioiltaan joku loisi |

| a miserable old bugaboo – | pois köyhän muodon entisen |

| and a weird flying creature | ja outo lentäväinen oisi |

| stretched a fragile wing and flew. | ja nostais siiven kevyen. |

| Ah limitless bright light: | Oi kimmellystä ilman pielen. |

| the gift of lyrical flight! | Oi rikkautta laulun kielen. |