Search results for "jarkko laine prize"

New from the archives

29 January 2015 | This 'n' that

Ulla-Lena Lundberg

Low-lying, sea-girt pieces of rock strewn across the sea midway between Finland and Sweden, the Åland Islands – known in Finnish as Ahvenanmaa – are a world unto themselves. In mind and spirit they are separate from both Finland (to which they technically belong) and Sweden, giving their inhabitants, writers included, a fascinating outsider status.

This week’s archive find, an extract from Leo, the first volume of Ulla-Lena Lundberg’s trilogy set in 19th-century Åland, offers a compelling portrait of the potent mix of cosmopolitanism and (literal) isolation of the islands’ seafaring community, in which the men sail the seas and the women stay at home.

Born on Åland in 1947, Lundberg is a writer of novels, short stories, poems and other essays; her work, she says, derives from her habit of sitting under the table as a small child and listening to what the grown-ups said. She received the Finlandia Prize in 2012 for her novel Is [‘Ice’], and the Tollander Prize in 2011.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues apace, with a total of 354 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

On life and death

23 November 2012 | In the news

Aki Ollikainen. Photo: Laura Malmivaara

On 15 November Helsingin Sanomat Literature Prize, the Helsinki newspaper’s prize for the best first work of the year, worth €15,000, was awarded for the 18th time.

The winner was journalist Aki Ollikainen (born 1973) with his first novel Nälkävuosi (‘The hunger year’, Siltala). The jury made the choice from 80 first works.

The hard years of 1867 and 1868 almost a tenth of the Finnish population died of hunger and diseases. Nälkävuosi portrays poor people in the country who are forced to leave home and look for any food they can find, and well-to-do gentlemen in town who can afford to amuse themselves with women, for example. This slim novel speaks of life and death; finally, after a deadly winter there will be new hope for better times.

Solzhenitsyn and Silberfeldt: Sofi Oksanen publishes a best-seller

25 April 2012 | In the news

Nobel Prize 1970: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

After falling out with her original publisher, WSOY, in 2010, author Sofi Oksanen – whose third novel, Puhdistus (Purge, 2008), has become an international best-seller – has founded a new publishing company, Silberfeldt, in 2011, with the aim of publishing paperback editions of her own books. Its first release was a paperback version of Oksanen’s second novel, Baby Jane.

Oksanen’s new novel, Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (‘When the pigeons disappeared’), again set in Estonia, will appear this autumn, published by Like (a company owned by Finnish publishing giant Otava).

However, in April Silberfeldt published a new, one-volume edition of the autobiographical novel The Gulag Archipelago by the Nobel Prize-winning author Alexandr Solzhenitsyn. This massive book was first published in the West in 1973, in the Soviet Union in 1989.

A Finnish translation was published between 1974 and 1978. Back in those days of Cold War self-censorship, Finnish publishers felt unable to take up the controversial book, and the first volume was eventually printed in Sweden. The work, finally published in three volumes, has long since been unavailable.

This time the 3,000 new copies of Solzhenitsyn’s tome sold out in a few days; a second printing is coming up soon. Oksanen regards the work as a classic that should be available to Finnish readers.

Alexandra Salmela: 27 eli kuolema tekee taiteilijan [27, or death makes the artist]

13 January 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

27 eli kuolema tekee taiteilijan

27 eli kuolema tekee taiteilijan

[27, or death makes the artist]

Helsinki: Teos, 312 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-302-8

€ 25.90, hardback

Alexandra Salmela (born 1980) is a Slovakian-born dramaturge and literature graduate who has settled in Finland. The book’s main character, Angie, lives in Prague and suffers from an idée fixe: all her idols, such as Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain and Janis Joplin, died, already famous, before their 28th birthdays, but her own literary career has yet to take wing. The frustrated Angie’s literature lecturer has a lake cottage in Finland where Angie meets an eco-minded family in the middle of the sparsely populated Finnish countryside. The clash between the chaotic family life and Angie’s wannabee artistic temperament are skilfully handled by Salmela, who has a secure grasp of literary means and a playful use of the Finnish language. Among the narrative voices employed by Salmela are the family’s cat and a piggy toy. Situational comedy, farce and a tragic Entführungsroman combine in the narratives, and the result is a malicious, funny work that pokes fun at everyone. The novel was awarded the Helsigin Sanomat newspaper’s prize for the best first novel, and appeared on the shortlist for the Finlandia Prize for Literature.

Poets, pastries and prizes

5 February 2015 | In the news

Joni Skiftesvik. Photo: Hilkka Skiftesvik

The Runeberg Prize for fiction is awarded to Joni Skiftesvik (67) for his autobiographical novel Valkoinen Toyota vei vaimoni (‘The white Toyota took my wife’).

Today, 5 February, is celebrated in Finland as the birthday of the poet J.L. Runeberg (1804-1877), known as the Finnish national poet, and writer – among many other things – of the lyrics of the national anthem.

In addition to the eating (in the Books from Finland offices, at least) of the rather delicious Runeberg cakes, it is also marked by the annual award of the Runeberg Prize, worth 10,000 euros.

The book tells the often harrowing story of Skiftesvik’s family, including illness, estrangement and death. In making the award, the jury commented: ‘This story appeals to the emotions, it touches the reader; but most important of all, after the book is closed, a miracle happens: its weighty content lives on in the mind, growing day by day. Many good novels have been written, but a masterpiece is recognised from its lasting effects.’

Runeberg’s favourite. Photo: Ville Koistinen

Science book of the year

13 January 2011 | In the news

A book on Islamic cuisine and food culture by Helena Hallenberg and Irmeli Perho has won the prize for the Finnish science book of the year (Vuoden tiedekirja), worth €10,000. The prize is awarded by the Suomen Tiedekustantajien Seura, Finnish Science Publishers’ Association, and Tieteellisten seurain valtuuskunta, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies.

A book on Islamic cuisine and food culture by Helena Hallenberg and Irmeli Perho has won the prize for the Finnish science book of the year (Vuoden tiedekirja), worth €10,000. The prize is awarded by the Suomen Tiedekustantajien Seura, Finnish Science Publishers’ Association, and Tieteellisten seurain valtuuskunta, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies.

Ruokakulttuuri islamin maissa (‘Food culture in Islamic countries’, Gaudeamus) explores both cultural and culinary history in the Near East and other Islamic countries since the sixth century, from the Prophet Muhammad to this day – and yes, the book also contains recipes. Both the authors are academics: Hallenberg is a scholar of Islamic saints and Chinese Muslims’ ideas of health, while Perho specialises in Islamic history of ideas and society.

Cimex lectularius: the bedbug. Photo: Wikipedia

And a honorary mention, worth €2,500, was awarded to a large work, with excellent illustrations, on Heteroptera, an extensive family of bugs, one of which is the bedbug – luckily unknown to most of us. The vast majority of people have no idea, either, of the fact that there are 22 endangered species of these bugs in Finland, the home of 507 different representatives of the Heteroptera family. So, Suomen luteet – johdatus luteiden mielenkiintoiseen maailmaan by Teemu Rintala and Veikko Rinne (‘The bugs of Finland – an introduction to the interesting world of the Heteroptera’, Tibiale) is a lively proof of the amazing biodiversity of Finland.

Funny peculiar

9 December 2011 | Articles, Comics, Non-fiction

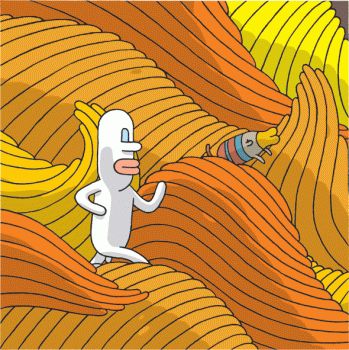

Samuel, the creation of Tommi Musturi (featured in Books from Finland on 7 May, 2010, entitled ‘Song without words’)

Comics? The Finnish word for them, sarjakuva, means, literally, ‘serial picture’, and lacks any connotation with the ‘comic’. The genre, which now also encompasses works called graphic novels, has been the subject of celebrations this year in Finland, where it has reached its hundredth birthday. Heikki Jokinen takes a look at this modern art form

Comics are an art form that combines image and word and functions according to its own grammatical rules. It has two mother tongues: word and image. Both of them carry the story in their own way. Images and sequences of images have been used since ancient times to tell stories, and stories, for their part, are the common language of humanity. The long dark nights of the stone age were no doubt enlivened by storytellers.

One of the pioneers of comics was the Swiss artist Rodolphe Töpffer. As early as 1837, he explained how his books, combinations of images and words, should be read: ‘This little booklet is complex by nature. It is made up of a series of my own line drawings, each accompanied by a couple of lines of text. Without text, the meaning of the drawings would remain obscure; without drawings, the text would remain without content. The whole gives birth to a sort of novel – but one which is in fact no more reminiscent of a novel than of any other work.’ More…

Best theatre, best play

16 March 2012 | In the news

On 11 March Finland’s theatre organisations gave their awards to last year’s best theatres and theatre-makers. Theatre of the Year was the Finnish National Theatre: according to the jury, it has both ‘opened all its doors, from cellar to attic’ and also left the building to make theatre and offered space for initiative. Audience figures have risen by more than 50,000, and the theatre’s repertoire has ‘cut keenly into the life and reality of contemporary audiences and the key national questions behind them without becoming bogged down in familiar stereotypes.’

The Finnish Dramatists’ Union awarded its Lea Prize for the Playtext of the Year, worth €5,000, to Pirkko Saisio’s HOMO! (This is Saisio’s fourth Lea Prize since 1986.) HOMO! is currently running, in a musical, or rather, operatic form in the National Theatre, in a production directed by the playwright herself; the composer is Jussi Tuurna.

In art as elsewhere, it is worth thinking about things from new angles – a few years back, for example, the National hardly did any musical theatre at all. (However, the company of actors in no way hinder the staging of musical theatre: under Tuurna’s direction, the entire cast burst into spectacular flower, alone and in chorus.) Besides, musical theatre was thought to be the province of the Helsinki City Theatre, where imported commercial musicals (Cats, Les Miserables, Mary Poppins etc) have lately represented a considerable part of the theatre’s income. On this production line, however, there are few chances for writers, composers and other theatremakers to develop a specifically Finnish musical theatre.

The Finnish National Theatre’s most recent success, Kristian Smeds’s Mr Vertigo also used original music, produced by young jazz musicians, which was on exactly the same wavelength as the text and its interpretation.

Portrait of the artist as a young boy

30 September 2010 | Reviews

Olli Jalonen. Photo: Katja Lösönen, 2008

Poikakirja (‘The boy’s own book’), Olli Jalonen’s 13th novel to date, continues an ongoing narrative often nominally examining the author’s own family history. In this novel the first-person narrator is the young ‘Olli’ in his first years at school, and his story is the present-tense monologue of a boy between the ages of 7 and 10. The choice of the present tense underlines a certain sense of ‘perpetual now’ in the intensive narrative of childhood.

Jalonen (born 1954) is one of the acknowledged masters of contemporary Finnish prose. His expansive novel Yksityiset tähtitaivaat (‘Private galaxies’, 1999) was an astonishing demonstration of the author’s desire to combine his cyclical understanding of history with a highly sensitive depiction of humanity. The work brought together three of his earlier novels and shaped them into an entirely new composition: at over 800 pages, it would be no exaggeration to call the resulting work a kind of symphony. More…