Search results for "jarkko/2011/04/2009/10/writing-and-power"

In pursuit of a conscience

19 March 2012 | Drama, Fiction

‘An unflinching opera and a hot-blooded cantata about a time when the church was torn apart, Finland was divided and gays stopped being biddable’: this is how Pirkko Saisio’s new play HOMO! (music composed by Jussi Tuurna) is described by the Finnish National Theatre, where it is currently playing to full houses. This tragicomical-farcical satire takes up serious issues with gusto. In this extract we meet Veijo Teräs, troubled by his dreams of Snow White, who resembles his steely MP wife Hellevi – and seven dwarves. Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

Dictators and bishops: Scene 15, ‘A small international gay opera’. Photographs: The Finnish National Theatre / Laura Malmivaara, 2011

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Veijo Teräs

Hellevi, Veijo’s wife and a Member of Parliament

Hellevi’s Conscience

Rebekka, Hellevi and Veijo’s daughter

Moritz, Hellevi and Veijo’s godson

Agnes af Starck-Hare, Doctor of Psychiatry

Seven Dwarves

Tom of Finland

Atik

The Bishop of Mikkeli

Adolf Hitler

Albert Speer

Josef Stalin

Old gays: Kale, Jorma, Rekku, Risto

Olli, Uffe,Tiina, Jorma: people from SETA [the Finnish LGBT association]

Second Lieutenant, Private Teräs, the men in the company

A Policeman

Big Gay, Little Gay, Middle Gay

William Shakespeare

Hermann Göring

Hans-Christian Andersen

Teemu & Oskari, a gay couple

The Apostle Paul

Father Nitro

Winston Churchill

SCENE ONE

On the stage, a narrow closet.

Veijo Teräs appears, struggling to get out of the closet.

Veijo Teräs is dressed as a prince. He is surprised and embarrassed to see that the audience is already there. He seems to be waiting for something.

He speaks, but continues to look out over the audience expectantly.

Snow White's spouse, Veijo (Juha Muje), and the dwarves. Photo: Laura Malmivaara, 2011

VEIJO

This outfit isn’t specifically for me, because… I mean, it’s part of this whole thing. This Snow White thing. I’m waiting for the play to start. Just like you are. My name is Veijo Teräs and I’m playing the point of view role in this story. Writers put point of view roles like this in their plays nowadays. They didn’t use to.

Just to be clear – this isn’t a ballet costume. I’m not going to do any ballet dancing, but I won’t mind if someone dances, even if it’s a man. Particularly if it’s a man. But I don’t watch. Ballet, I mean. Not at the opera house, or on television, or anywhere, and I have no idea why we had to bring up ballet – or I had to bring it up – because this is a historical costume, so it’s appropriate. This is what men used to wear, real men like Romeo and Hamlet, or Cyrano de Bergerac. But we in the theatre these days have a hell of a job getting an audience to listen to what a man has to say when he’s standing there saying what he has to say in an outfit like this. People get the idea that it’s a humorous thing, but this isn’t, this Snow White thing, where I play the prince. Snow White is waiting in her glass casket, she died from an apple, which seems to have become the Apple logo, Lord knows why, the one on the laptops you see on the tables of every café in town. More…

Trial and error?

31 December 2008 | Archives online, Essays, On writing and not writing

If you want to write, you need to do it every day, says the author Monika Fagerholm. Trial and error are necessary for her – and so is not being afraid of getting lost in the woods in the process, because only then can amazing things be found

Writers write and writers write every day. I remember seeing this in one of those inspirational guides on writing I enjoy reading – even if they don’t necessarily help you in pursuing your daily writing as much as you would hope. At the worst, they give you a kind of exhausting energy which just leaves you drained. And yes, turning to these kinds of manuals almost always involves an element of desperation; you don’t need advice when everything is going great. More…

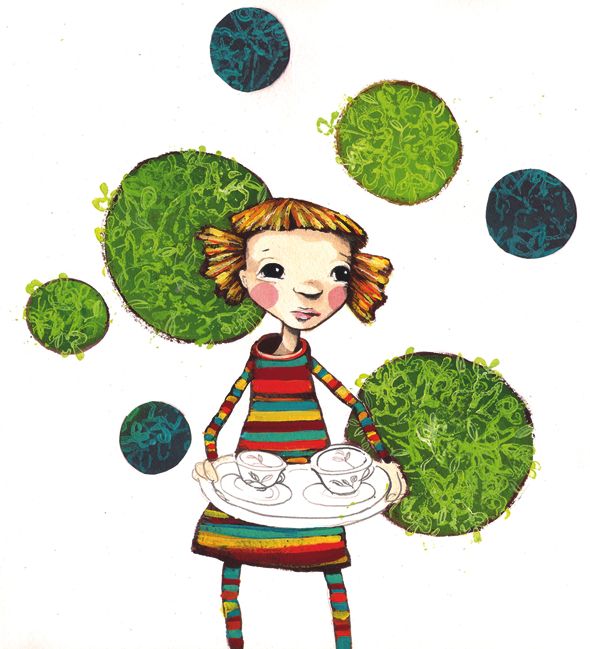

Once upon a time…

13 January 2012 | Articles, Non-fiction

Sari Airola's illustration in Silva och teservisen som fick fötter (‘Silva and the tea set that took to its feet’, Schildts) by Sanna Tahvanainen

The future of book publishing is not easy to predict. Books for children and young people are still produced in large quantities, and there’s no shortage of quality, either. But will the books find their readers? Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen takes a look at the trends of 2011, while in the review section we’ve picked out a selection of last year’s best titles

The supply of titles for children and young adults is greater than ever, but the attention the Finnish print media pays to them continues to diminish. Writing about this genre appears increasingly ghettoised, featuring only in specialist publications or internet chat rooms and blogs.

Yet, defying the prospect of a recession, Suomen lastenkirjakauppa, a bookshop specialising in children’s literature, was re-established in central Helsinki in autumn 2011, following a ten-year break. Pro lastenkirjallisuus – Pro barnlitteraturen ry, the Finnish society for the promotion of children’s literature, has been making efforts to found a Helsinki centre dedicated to writing and illustration for children. The society made progress in this ambition when it organised a pilot event in May 2011. More…

Future, fantasy and everyday life: books for young readers

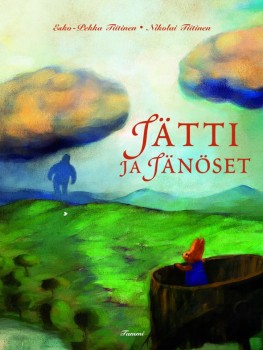

24 January 2013 | Articles, Children's books, Non-fiction

A giant meets the bunnies: a new story by Esko-Pekka Tiitinen, illustrated by Nikolai Tiitinen

Fantasy novels and dystopias feature in the new Finnish fiction for young readers; popular children’s books are recycled – stories and illustrations are adapted to new media and for new age groups. Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen takes a look at new books for young readers published in 2012

All new mothers in Finland receive a ‘maternity package’ from the state containing items for the baby (including bedding, clothing and various childcare products) intended to give each baby a good start in life. This tradition, which started in 1938, is believed to be the only such programme in the world.

Each package also contains the baby’s first book, traditionally a sturdy board book by a Finnish author. The past few years have seen more original board books published in Finland than ever before: they are doing well in competition alongside books translated from other languages. Board books for babies have become a focus for Finnish illustrators and graphic artists. These books, with their simple visual language, have taken on a retro look.

History was made with the Finlandia Junior award, when for the first time the prestigious prize was given to a picture book originally written in Finland-Swedish: Det vindunderliga ägget (‘A most extraordinary egg’, Schildts & Söderströms) by Christel Rönns. The award can also be seen as an acknowledgement of the brave, experimental Finland-Swedish children’s picture books that are being published these days. Finnish-language picture books, on the other hand, are still crying out for more figures to shake up traditional practices. More…

Writing and power

15 October 2009 | This 'n' that

Speaking in the cold: the Chairperson of the Lahti Writers' Union, Jarmo Papinniemi (left), and the Bosnian writer Igor Štiks (right) listen to Riina Katajavuori's presentation

The theme of the biannual International Writers’ Reunion (LIWRE) which took place in Lahti, southern Finland, in June for the 24th time, was ‘In other words’.

The theme inspired the participants (54 in total, foreign and Finnish) to talk, among other things, about the power of the written word in strictly controlled regimes, about fiction that retells human history, about the difference between the language of men and women, about languages that have been considered – by those who rule, naturally – ‘better’ than other languages. Eleven presentations are available in English.

Speaking about the birth of her latest collection of poems, Kerttu ja Hannu (‘Gretel and Hansel’, 2007), the Finnish writer Riina Katajavuori described in her presentation the need to use other words. In her case they were those of poetry, in retelling a tale; here are some extracts (scroll down!). More…

Locomotive

30 June 1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Dockskåpet (‘The doll’s house’). Introduction and translation by W. Glyn Jones

What I am about to write might perhaps seem exaggerated, but the most important element in what I have to tell is really my overriding desire for accuracy and attention to detail. In actual fact, I am not telling a story, I am writing an account. I am known for my accuracy and precision. And what I am trying to say is intended for myself: I want to get certain things into perspective.

It is hard to write; I don’t know where to begin. Perhaps a few facts first. Well, I am a specialist in technical drawings and have been employed by Finnish Railways all my life. I am a meticulous and able draughtsman; in addition to that I have for many years worked as a secretary; I shall return to this later. To a very great extent my story is concerned with locomotives; I am consciously using this slightly antiquated word locomotive instead of loco, for I have a penchant for beautiful and perhaps somewhat antediluvian words. Of course, I often draw detailed sketches of this particular kind of engine as part of my everyday work, and when I am so engaged I feel no more than a quiet pride in my work, but in the evenings when I have gone home to my flat I draw engines in motion and in particular the locomotive. It is a game, a hobby, which must not be associated with ambition. During recent years I have drawn and coloured a whole series of plates, and I think that I might be able to produce a book of them some time. But I am not ready yet, not by a long way. When I retire I shall devote all my time to the locomotive, or rather to the idea of the locomotive. At the moment I am forced to write, every day; I must be explicit. The pictures are not sufficient. More…

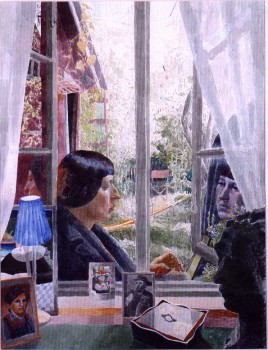

A light shining

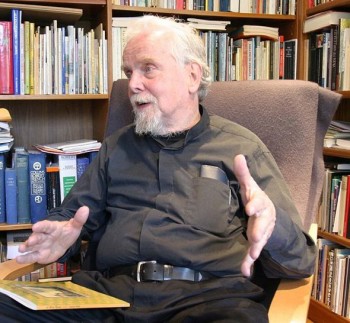

28 July 2011 | Essays, Non-fiction

Portrait of the author: Leena Krohn, watercolour by Marjatta Hanhijoki (1998, WSOY)

In many of Leena Krohn’s books metamorphosis and paradox are central. In this article she takes a look at her own history of reading and writing, which to her are ‘the most human of metamorphoses’. Her first book, Vihreä vallankumous (‘The green revolution’, 1970), was for children; what, if anything, makes writing for children different from writing for adults?

Extracts from an essay published in Luovuuden lähteillä. Lasten- ja nuortenkirjailijat kertovat (‘At the sources of creativity. Writings by authors of books for children and young people’, edited by Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen; The Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature & BTJ Kustannus, 2010)

What is writing? What is reading? I can still remember clearly the moment when, at the age of five, I saw signs become meanings. I had just woken up and taken down a book my mother had left on top of the chest of drawers, having read to us from it the previous day. It was Pilvihepo (‘The cloud-horse’) by Edith Unnerstad. I opened the book and as my eyes travelled along the lines, I understood what I saw. It was a second awakening, a moment of sudden realisation. I count that morning as one of the most significant of my life.

Learning to read lights up books. The dumb begin to speak. The dead come to life. The black letters look the same as they did before, and yet the change is thrilling. Reading and writing are among the most human of metamorphoses. More…

The coder’s Latin

30 October 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

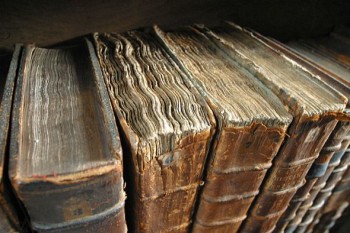

Pleasant interface still? Old book bindings (Merton College library, Oxford, UK). Photo: Wikipedia

Writing is arguably brain-control technology, notes our columnist Teemu Manninen. Writing might not be on its way out, at least not quite yet, he thinks, but the printed book might not stay with us for ever. And would that be a happier world?

When the future of literature is discussed, either here in Finland and elsewhere, topics usually revolve around changes in the economics and practicalities of reading, writing, and publishing: how will writers and publishers get paid, and how can readers find more books to read.

What is taken for granted in these instances is that literature itself will continue to be something that exists in a recognisable way – which itself of course implies that writing itself will remain a viable mass medium for the transmission of information over the transcendent, enormous, unfathomable gulfs of space and time, as it has been for thousands of years. More…

Literary prizes: the Dancing Bear 2009

21 May 2009 | In the news

Sanna Karlström. - Photo: Irmeli Jung

This year’s Dancing Bear Poetry Prize, worth €3,500, has gone to Sanna Karlström (born 1975) for her third collection of poems, Harry Harlow’n rakkauselämät (‘The love lives of Harry Harlow’, WSOY, 2008). The prize is awarded every May by the Finnish Broadcasting Company to a book of poetry published the previous year. It was given this year for the 16th time.

The collection, containing short, condensed tales of love and lovelessness, forms a fragmented portrait of the American psychologist Harry Harlow who, in the 1950s, made notorious experiments with young rhesus monkeys in which he separated them from their mothers.

Chosen by a jury of three radio journalists, Barbro Holmberg, Marit Lindqvist and Tarleena Sammalkorpi, and the poet Risto Oikarinen, the other shortlisted authors were Ralf Andtbacka, Kari Aronpuro, Eva-Stina Byggmästar, Jouni Inkala and Silja Järventausta.

The Finlandia prizes: Non-fiction, Junior

28 November 2013 | In the news

Ville Kivimäki. Photo: Pertti Nisonen

The Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2013, worth €30,000, was awarded on 21 November to the historian Ville Kivimäki for his book Murtuneet mielet. Taistelu suomalaissotilaiden hermoista 1939–1945 (‘Broken minds. The battle ofor the nerves of Finnish soldiers 1939–1945’, WSOY).

The other works on the shortlist of six were as follows: 940 päivää isäni muistina (‘940 days as my father’s memory’, Teos; a book on Alzheimer’s disease) by Hanna Jensen, Kokottien kultakausi: Belle Epoquen mediatähdet modernin naiseuden kuvastimina (‘The golden era of the cocottes: the media stars of Belle Epoque as mirrors of modern femininity’, Finnish Literature Society) by Harri Kalha, Viipuri 1918 (‘Vyborg 1918’, Siltala) by Teemu Keskisarja, Suomi öljyn jälkeen (‘Post-oil Finland’, Into) by Rauli Partanen, Harri Paloheimo and Heikki Waris and Vapaalasku – tieto, taito, turvallisuus (‘Freestyle – knowledge, skill, safety’, Kustannus Oy Vapaalasku) by Matti Verkasalo, Jarkko-Juhani Henttonen and Kai Arponen.

The prize-winner was chosen by the director of the Ateneum Art Museum, Maija Tanninen–Mattila. In her celebratory speech she said: ‘The symptoms of many psychologically disturbed soldiers remained untreated during the war. For many, their symptoms appeared only after the war. Their experiences have remained unexpressed in language, the history of those who lack history. Ville Kivimäki has given voice to these experiences… and succeeded in writing a book that speaks across the generations.’

In his acceptance speech Ville Kivimäki (born 1976) commented: ‘The great majority of the war generation is now dead, and the words of a youngish scholar cannot, even when successful, reach those traumatic experiences whose depth we can never fully understand. But all the same, I would like to take this opportunity to say something that should have been said years ago: the psychological injuries of the war were war wounds in exactly the same sense as physical ones. In the end anyone could suffer a psychological breakdown.’

Kreetta Onkeli. Photo: Jouni Harala

The Finlandia Junior Prize 2013 was awarded on 26 November, also worth €30,000. It went to Kreetta Onkeli for her book Poika joka menetti muistinsa (‘The boy who lost his memory’, Otava).

Arto, 12, gets such a massive fit of laughter that he loses his memory and needs to find his identity and his home in contemporary Helsinki.

The winner was chosen from the shortlist of six by Jarno Leppälä, a media personality and member of the popular stunt group Duudsonit, the Dudesons. At the award ceremony he said:

‘Poika joka menetti muistinsa is, in my opinion, a well-written story about how young people in society are put on the same starting line and expected to do equally well in all circumstances – often irrespective of the fact that their starting points may actually be very different, and completely independent of the young people themselves.’

Kreetta Onkeli (born 1970) explained in her award speech how her aim was to write a proper, old-fashioned novel for children: ‘Not hundreds of pages of magic tricks but ordinary, real contemporary life that children could identify with.’ In her opinion the current, massive trend of fantasy has narrowed the scope of children’s literature.

The following five books made it on to the shortlist: Poika (‘The boy’, Like), about a boy who feels he was born in the wrong gender by Marja Björk, Hipinäaasi, apinahiisi (onomatopoetic pun, ‘Donkeymonkey’, Tammi), about bullying and friendship, written by Ville Hytönen and illustrated by Matti Pikkujämsä, Isä vaihtaa vapaalle (‘Father on his own time’, WSOY), an illustrated story about children with too busy parents, written by Jukka Laajarinne and illustrated by Timo Mänttäri, Aapine (‘ABC’, Otava), an illustrated primer written by Heli Laaksonen in her own south-western dialect and illustrated by Elina Warsta and Vain pahaa unta (‘Just a bad dream’, WSOY) by graphic designer and writer Ville Tietäväinen and his daughter Aino, a book on a child’s nightmares.

Finlandia literary prizes are awarded by Suomen Kirjasäätiö, The Finnish Book Foundation, established in 1983.

The first Finlandia Prize for Fiction was awarded in 1984. This year it will be announced on 3 December.

Cityscapes

23 February 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Photographer Stefan Bremer’s home town, Helsinki, provides endless inspiration, material and atmospheric. For forty years Bremer has been recording views of the maritime city, its changing seasons, its cultural events, its people. These images are from his new book – entitled, simply, Helsinki (Teos, 2012)

City kids: day-care outing in Töölönlahti park. Photo: Stefan Bremer, 2010

When I was a child, Helsinki seemed to me a grey and sad town. Stooping, quiet people walked its broad streets. The colours of the houses had been darkened by coal smoke over the years, and new buildings were coated a depressing grey.

A lot has since changed. Today, Helsinki is younger than it was in my youth. More…