Search results for "jarkko/2011/04/2010/05/2009/10/writing-and-power"

Arne Nevanlinna: Hjalmar

5 November 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Hjalmar

Hjalmar

Helsinki: WSOY, 2010. 294 p.

ISBN 978-951-0-36700-1

€29, hardback

‘Jansson!’ Hjalmar, the protagonist of Arne Nevanlinna’s second novel, is repeatedly woken by voices barking his surname at him. The people shouting at him are primary school teachers, commanding officers, nurses, psychiatrists and his bosses; these figures collectively serve as a sort of Orwellian ‘Big Brother’ figure, or Hjalmar’s social superego. At the core is penniless bohemian office drone Hjalmar’s relationship to his boss, Börje, who personifies the archetype of the Finnish banker, both idolised and loathed. Hjalmar eventually rises up from his lowly position into the opposition, aided by several picaresque characters and his own ‘pokeresque’ skills as a gambler. Arne Nevanlinna (born 1925), an architect and essayist, began writing fiction late in his career: his first novel, Marie (2008), was a runaway success. It tells of a lady from the cream of Strasbourg society who had been married off to Finland and lived in isolation to the age of a hundred. Hjalmar does not quite match its predecessor in terms of quality, but the elegance of old patrician clans persists in its enjoyable irony.

Northern exposure

21 June 2012 | Reviews

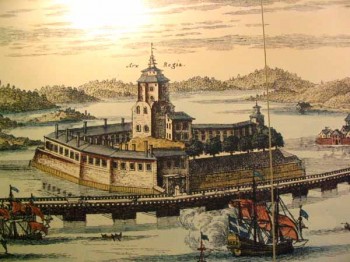

Between Helsinki and St Petersburg: Vyborg. Illustration of Vyborg Castle by an unknown artist, 1709, Wikimedia

Tony Lurcock

‘Not So Barren or Uncultivated’. British travellers in Finland 1760–1830

London: CB Editions, 2010. 230 p.

ISBN 9-780956-107398

£10.00, paperback

Finland is not unique in raising scholars who have often attempted to treat historical travellers’ accounts as source material for historical facts, and then prove how ‘wrong’ they are in relation to reality. This is an unproductive way in which to read them: travel books are nearly always based on the authors’ own country and experiences projected on what they encounter abroad.

Paradoxically, much of what was written about foreign countries in the past was really about conditions and problems in the author’s own land, and can be understood only against that background – something that also emerges in this book about British travellers in Finland. More…

Grim(m) stories?

30 April 2010 | Letter from the Editors

‘There’s not been much wit and not much joy, there’s a lot of grimness out there.’

‘There’s not been much wit and not much joy, there’s a lot of grimness out there.’

This comment on new fiction could have been presented by anyone who’s been reading new Finnish novels or short stories. The commentator was, however, the 2010 British Orange Prize judge Daisy Goodwin, who in March complained about the miserabilist tendencies in new English-language women’s writing. More…

John Lagerbohm & al.: Me puolustimme elämää. Naiskohtaloita sotakuvien takaa [We were defending life. The fates of women behind pictures of war]

21 April 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

John Lagerbohm & Jenni Kirves & Olli Kleemola

John Lagerbohm & Jenni Kirves & Olli Kleemola

Me puolustimme elämää. Naiskohtaloita sotakuvien takaa

[We were defending life. The fates of women behind pictures of war]

Esipuhe [Foreword]: Elisabeth Rehn

Helsinki: Otava, 2010. 176 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-24660-2

€ 41, hardback

The women’s narratives of the Winter War (1939–40) and the Continuation War (1941–44) in this book are complemented by memoirs and academic writing, as well as journalistic extracts, personal recollections and interviews. It focuses on the status of women in wartime, showing that, in addition to the members of the Lotta Svärd auxiliary organisation, women carried a great deal of responsibility in a variety of roles, taking up traditionally male-dominated work in ports and mines. During the war years, the duty to work applied to all citizens aged 15 and up for whom various tasks could be assigned. One of the difficult jobs for ‘Lottas’ on the front line was placing the bodies of fallen soldiers into coffins and sending them home for burial. To maintain morale, it was important to the women to derive joy even from little things, and that humour comes through in this book as well. There is a wide range of photographic material, some of which comes from private collections.

Siiri Enoranta: Painajaisten lintukoto [Sweet haven of nightmares]

24 January 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Painajaisten lintukoto

Painajaisten lintukoto

[Sweet haven of nightmares]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2012. 330 pp.

ISBN 978-951-0-38932-4

€26.90, hardback

Siiri Enoranta’s debut novel, Omenmean vallanhaltija (‘The Ruler of Omenmea’, Robustos, 2009) was nominated for the Finlandia Junior award, while another of her novels, Gisellen kuolema (‘The death of Giselle’) was nominated for the Runeberg Prize. Painajaisten lintukoto marks a departure from the genre Enoranta had focused on in her previous works. Her books incorporate the joy of spellbinding, spontaneous fantasy and skill at creating ever more uncanny settings. This novel is situated in the vacillating borderlands between sleep and the waking world. Lunni is a teenage boy who has been set a challenging task of overcoming nightmares and restoring natural sleep to people. The boy is joined by Tui, a mechanical girl. Other important figures in the story are giant tame birds that help Lunni and Tui get from place to place. The prose of Siiri Enoranta (1987) is lyrical, but it also contains points of contact for fans of fantasy writing of many different ages.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

From the land of abundant reindeer…

17 March 2011 | This 'n' that

Rangifer tarandus, Finnish Lapland. Photo: Grand-duc (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Grand-Duc)

Is Finland, a land of reindeer, ‘dense pine forests and deep snows’ also a ‘quiet literary landscape’?

Not exactly, as we at Books from Finland hope we are demonstrating. And over on the Bookslut website, Bonnie B. Lee comes to the same conclusion, after having mused about the reindeer (yes: in Helsinki you find tasty chunks of them in the freezer boxes of any foodstore) and reading three Finnish novels in English translation.

The novels Lee reviews are Purge by Sofi Oksanen (Puhdistus, 2008, translated by Lola Rogers, published last year), When I forgot by Elina Hirvonen (Että hän muistaisi saman, 2005, translated by Douglas Robinson, published in 2009) and The Year of the Hare by Arto Paasilinna (Jäniksen vuosi, 1975, first published in an English translation by Herbert Lomas in 1995, reprinted as a Penguin edition last year).

We have just entered the Year of the Rabbit, in recognition of which Paasilinna’s book (about a man who rejects his old life and goes roaming the wildernesses with a hare as his only companion) has appeared on the tables of large bookstores in the US. ‘The Year of the Hare is only the most Finnish, and perhaps most antically Zen-ish, of a shelf-load of books that tell us to find and live by our own ideas of contentment,’ said The Wall Street Journal.

The traumatic experiences of war and Finland’s deep forests are the common feature of these novels, Bonnie B. Lee finds. She also opines that ‘melancholy pervades the Finnish psyche’, and that ‘Finland vies with Hungary for highest suicide rate in Europe‘. Oh, but this latter is no longer true: number one on a World Health Organisation suicide rates list is Lithuania, followed by Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia and Latvia – Finland is number six.

Lee is clearly intrigued by her travels in contemporary Finnish literature. ‘The search for identity, a reckoning with a troubled past, and an outsider’s view looking in,’ she comments, ‘are all the stuff of great writing, and Finland is poised to continue to produce poignant and introspective literature that we can appreciate now that English translators have begun the work.’

Poignant and introspective or occasionally funny and fantastical, this is the work we try to offer an early glimpse of, in translation, at Books from Finland. Stay with us!

A long list of good novels

27 November 2014 | In the news

The longlist for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award 2015 has been announced and, among the 142 translated novels – from 39 countries and 16 original languages – are two from Finland.

The longlist for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award 2015 has been announced and, among the 142 translated novels – from 39 countries and 16 original languages – are two from Finland.

Mr Darwin’s Gardener by Kristina Carlson (Peirene Press, UK, 2012), a novel set in the 1860s England, is translated by Emily and Fleur Jeremiah (see the extracts in Books from Finland).

Cold Courage, a thriller by Pekka Hiltunen (Hesperus Press, UK), is translated by Owen Witesman. Both entries were nominated by Helsinki City Library.

Among the authors writing in English are Margaret Atwood, J.M. Coetzee, Roddy Doyle, Stephen King, Jhumpa Lahiri, Thomas Pynchon and Donna Tartt.

This literary award was established by Dublin City, Civic Charter in 1994. Nominations are made by libraries in capital and major cities throughout the world, on the basis of ‘high literary merit’. In order to be eligible for consideration in 2015 a novel translated into English must be first published in the original language between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2013.

The award for a translated novel is worth €75,000 to the author, €25,000 to the translator. The shortlist of ten titles will be announced by an international panel of judges in April 2015, the winner in June.

We’ll be keeping our fingers crossed for our ex-Editor-in-Chief Kristina Carlson!

The house the seniors built

27 November 2009 | Reviews

Yours and mine: the common dining room at Sprint

Maija Dahlström – Sirkka Minkkinen

Loppukiri. Vaihtoehtoista asumista seniori-iässä

[Sprint: alternative living for seniors]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2009. 232 p., ill.

ISBN 978-9510-4322-9

€ 32.90, paperback

‘Your elderly mother just told you she fell in the bathroom last night at 4 a.m. Now what?’ advertises the Visiting Nurse Service of New York in the New York Times. Aging people and their desire to live in their own homes is a pressing question around the world. People feel concern over their own living arrangements and those of their loved ones. Living arrangements somewhere between being in one’s own home or in a care facility are sought by many, but there are few of these options available. More…

Vesa Karonen & Panu Rajala: Yrjö Jylhä, talvisodan runoilija [Yrjö Jylhä, poet of the Winter War]

11 December 2009 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Yrjö Jylhä, talvisodan runoilija

Yrjö Jylhä, talvisodan runoilija

[Yrjö Jylhä, poet of the Winter War]

Helsinki: Otava, 2009. 351 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-23840-9

€ 35, hardback

Yrjö Jylhä (1903–1957) was a poet and translator whose collection of poems entitled Kiirastuli (‘Purgatory’), published in 1941 after the Winter War, is one of the most popular works of Finnish verse. Jylhä served as commander of a Karelian army company during the Winter War. A certain sternness, melancholy and pessimism about life are considered to be characteristic of Jylhä’s writing. The author of this book, the first biography of Jylhä, had access to new source materials including letters written from the front. The war meant not only great change for Jylhä as a writer, but also a test of his own limits as a leader and a soldier among other men. After the war, Jylhä’s reputation began to wane – partly for political reasons, as people took a more dismissive attitude towards war poetry about the Finnish fatherland. Jylhä suffered from a serious illness and artistic frustration in his middle age, which led him to take his own life.

The painter who wrote

6 October 2014 | Non-fiction, Reviews

Brev från Tove Jansson

Brev från Tove Jansson

Urval och kommentarer Boel Westin & Helen Svensson

[Letters from Tove Jansson, selected and commented by Boel Westin & Helen Svensson]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2014. 491 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-52-3408-7

€34.90

In Finnish (translated by Jaana Nikula):

Kirjeitä Tove Janssonilta

ISBN 978-951-52-3409-4

Nothing could be more mistaken than to describe Tove Jansson as ‘Moominmamma’. In her statements she was both cutting and complex – conflict-ridden and full of paradoxes. And she was nobody’s mamma.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) became world famous (especially ‘big’ in Japan) with her Moomins – the characters of her illustrated books for children (1945–1970) – and her books for adults are a part of her work that is at least as interesting. Her training, ambition and artistic passion were, however, focused on painting.

Anyone who has read Boel Westin’s excellent biography – now available in English, Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words – ‘knows’ all this, but to experience it through Jansson’s own letters, in an alternating process of reflection and recreation, brings the problems close to the reader in quite a different way: one that is shocking, but also deeply human. More…

Happy days, sad days

28 February 2013 | Reviews

Pekka Tarkka

Pekka Tarkka

Joel Lehtonen II. Vuodet 1918–1934

[Joel Lehtonen II. The years 1918–1934]

Helsinki: Otava, 2012. 591 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-25924-4

€38.50, hardback

A well-meaning bookseller’s idealism, inspired by Tolstoyan ideology, is brought crashing down by the laziness and ingratitude of the man hired to look after his estate: conflicts between the bourgeoisie and the ‘ordinary folk’ are played out in heart of the Finnish lakeside summer idyll in Savo province.

Taking place within a single day, the novel Putkinotko (an invented, onomatopoetic place name: ‘Hogweed Hollow’) is one of the most important classics of Finnish literature. Putkinotko was also the title of a series (1917–1920) of three prose works – two novels and a collection of short stories – sharing many of the same characters [here, a translation of ‘A happy day’ from Kuolleet omenapuut, ‘Dead apple trees’, 1918] .

In 1905 Joel Lehtonen bought a farmstead in Savo which he named Putkinotko: it became the place of inspiration for his writing. With an output that is both extensive and somewhat uneven, the reputation of Joel Lehtonen (1881–1934) rests largely on the merits of his Putkinotko, written between 1917 and 1920. More…

A long dream

9 October 2009 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Jälkikasvu (‘Offspring’, Otava, 2009)

‘I was eating a late breakfast, without a care in the world, when it happened.’

He snaps off the recorder. He has said the same thing three times now, but he always loses his train of thought right there. Why is it so difficult to continue? In his mind, the next part feels quite clear, but the words simply won’t come out of his mouth. He ought to say that his wife left him yesterday, on the twelfth of February, at 10:48 AM, following a three-minute fifteen-second briefing. More…

Memory in my hands

19 August 2010 | Fiction, poetry

A couple of years ago Timo Harju chose the non-military alternative to national service and was detailed to work at an old people’s home. Its director warned him that its inhabitants were ‘no sweet old grannies and grandpas’. Harju thought this might be a joke. In his first collection of poems, entitled Kastelimme heitä runsaasti kahvilla (‘We watered them abundantly with coffee’, Ntamo, 2009), he patiently gathers fragments of dreams and fears, memories and forgotten songs in the house of oblivion, treating them with gentle empathy. Commentary by Pia Ingström

Ward A5, Thursday

The clouds in the nursing home corridors, sky-open springlike after a bathe

and forgotten, in a frayed blue dressing-gown beside an osiery.

The grannies in the nursing home corridors, the last beautiful pride

you keep in a small wooden box behind your forehead:

if the lid opens by accident all the things may drop to the floor

topsy-turvy you won’t be able to find them, your back won’t let you

you won’t recognise them any more even if you do,

the springtime tears your insides to pieces.

Here they come, the grannies.

Better to stay here indoors, the journey to the dining room is a rough one

exposed like this

a long way and all by sleigh.

You stare at the keyhole: the clouds are coming. More…