Search results for "moomins"

Hip hip hurray, Moomins!

22 October 2010 | This 'n' that

Partying in Moomin Valley: Moomintroll (second from right) dancing through the night with the Snork Maiden (from Tove Jansson’s second Moomin book, Kometjakten, Comet in Moominland, 1946)

The Moomins, those sympathetic, rotund white creatures, and their friends in Moomin Valley celebrate their 65th birthday in 2010.

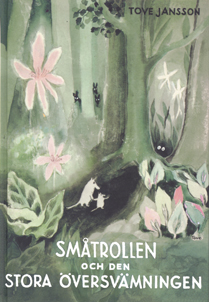

Tove Jansson published her first illustrated Moomin book, Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (‘The little trolls and the big flood’) in 1945. In the 1950s the inhabitants of Moomin Valley became increasingly popular both in Finland and abroad, and translations began to appear – as did the first Moomin merchandise in the shops.

Jansson later confessed that she eventually had begun to hate her troll – but luckily she managed to revise her writing, and the Moomin books became more serious and philosophical, yet retaining their delicious humour and mild anarchism. The last of the nine storybooks, Moominvalley in November, appeared in 1970, after which Jansson wrote novels and short stories for adults.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) was a painter, caricaturist, comic strip artist, illustrator and author of books for both children and adults. Her Moomin comic strips were published in the daily paper the London Evening News between 1954 and 1974; from 1960 onwards the strips were written and illustrated by Tove’s brother Lars Jansson (1926–2000).

Tove’s niece, Sophia Jansson (born 1962) now runs Moomin Characters Ltd as its artistic director and majority shareholder. (The company’s latest turnover was 3,6 million euros).

For the ever-growing fandom of Jansson there is a delightful biography of Tove (click ‘English’) and her family on the site, complete with pictures, video clips and texts.

The world now knows Moomins; the books have been translated into 40 languages. The London Children’s Film Festival in October 2010 featured the film Moomins and the Comet Chase in 3D, with a soundtrack by the Icelandic artist Björk. An exhibition celebrating 65 years of the Moomins (from 23 October to 15 January 2011) at the Bury Art Gallery in Greater Manchester presented Jansson’s illustrations of Moominvalley and its inhabitants.

In association with several commercial partners in the Nordic countries Moomin Characters launched a year-long campaign collecting funds to be donated to the World Wildlife Foundation for the protection of the Baltic Sea. Tove Jansson lived by the Baltic all her life – she spent most of her summers on a small barren island called Klovharu – and the sea featured strongly in her books for both children and adults.

Moomins on the beach

23 April 2015 | This 'n' that

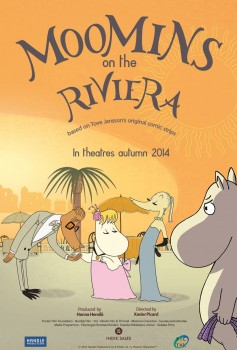

A new, Finnish-French, animated movie sees the Moomin family caught up in a typhoon that lands them among the fleshpots of the French Riviera.

A new, Finnish-French, animated movie sees the Moomin family caught up in a typhoon that lands them among the fleshpots of the French Riviera.

Based not on Tove Jansson’s children’s books, but on a cartoon strip drawn by Tove and her brother, Lars, that ran in the London Evening Standard newspaper between 1954 and 1970, Moomins on the Riviera offers the Moomins a whole host of new experiences.

The plot draws the experiences of Tove and her mother on holiday in the south of France. The bedraggled family takes up residence in the royal suite of the Grand Hotel, where they are initially quite unaware that they will have to pay for the privilege. Moominpappa makes friends with the aristocratic Marquis de Mongaga and affects the surname ‘de Moomin’; the Snorkmaiden, meanwhile, is dazzled by the charms of a playboy by the name of Clark Tresco. Overwhelmed – and worried about how the family can stick together in the face of all these new experiences – Moomintroll and Moominmamma decide to move to the beach, and seek shelter under their shipwrecked boat.

The trailer for the film, which is a co-production between Handle Productions of Finland Pictak of France, shows a hand-drawn animation style which stays very close to Tove Jansson’s original drawings – something which will delight the many Moomin fans who were horrified by the cute, balloon-like characters in the popular Japanese TV animation.

The film’s director is Xavier Picard, and its producer and co-director Hanna Hemilä. It opens in London on 22 May.

Smart Moomins

27 June 2012 | This 'n' that

From page to screen: Tove Jansson's classic

‘Here’s little Moomintroll, none other,

Hurrying home with milk for Mother,’

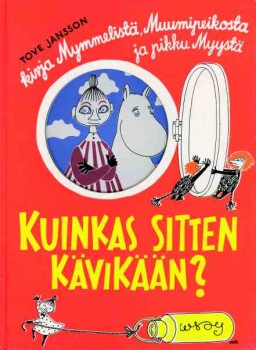

are the opening lines of Tove Jansson’s classic 1952 illustrated children’s tale of a sister lost and found, The Book about Moomintroll, Mymble and Little My, in the English poet and novelist Sophie Hannah’s beguiling translation. (Swedish original: Hur gick det sen? Boken om Mymlan, Mumintrollet och Lilla My; illustration: the Finnish version.)

The book has now been released as a smartphone app by the London publisher Sort Of Books and Helsinki’s WSOY in collaboration with the Finnish developer Spinfy.

At the tap of a finger, birds fly, forest creatures crawl up and down tree-trunks, flowers open and close, fish jump and hattifatteners wiggle. Unlike in the Japanese animated cartoons that have done so much to make the Moomins well-known worldwide, this is achieved without doing any violence to Jansson’s original graphics.

The app can be played either in text or, for very small children, read-to mode, voiced by the actor Sam West. Three more Moomin apps are scheduled for release later this year.

Moomins, and the meanings of our lives

21 December 2012 | This 'n' that

The first ever Moomin story, 1945

Tove Jansson’s Moomin books are widely cherished by children and adults alike. They are funny and charming yet haunting and profound. Lovable Moomintroll; practical and sensible Moominmama; spiky Little My; the terrifying yet complex monster, Groke – Jansson’s creations linger in the mind.

The first ever Moomin book – The Moomins and the Great Flood (Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen, 1945) – was published in the UK in October by Sort Of Books, but Jansson’s writing for adults is also achieving recognition in the English-speaking world.

A Winter Book, a selection of 20 stories by Jansson (Sort Of Books, 2006) was the trigger for a recent event on London’s South Bank. Along with journalist Suzi Feay and writer Philip Ardagh, I was invited to talk about Jansson’s work in general and about these stories in particular.

As Ali Smith notes in her fine introduction to the collection, the texts are ‘beautifully crafted and deceptively simple-seeming’. They are, as she puts it ‘like pieces of scattered light’. She also refers to the stories’ ‘suppleness’ and ‘childlike wilfulness’.

‘The Dark’, for example, offers an apparently random set of snapshots of childhood. Arresting images abound – swaying lamps over an ice rink, swirls in the pattern of a carpet that turn into terrible snakes – to create a tapestry of childhood. It’s like a dream: of ice and fire, fear and safety, a mixture that recalls the secure yet scary world of Moomin valley.

‘Snow’, too, conjures childhood fear. The house that features in this story is unhomely or uncanny, to refer to Freud, and seems haunted by the ghosts of other families. The story ends with the shared resolution between mother and child to return to a place of safety: ‘So we went home.’

Tove Jansson (1914–2001)

The combination of scariness and safety, of comfort and unease, is one of the things that makes Jansson (1914–2001) such a powerful writer, not only for children – although questions of security and fear might have especial resonance in early life – but also for adults, who continue to be haunted by the unknown, but also tempted by it.

The South Bank event also gave participants and audience the chance to talk about other works by Jansson. The Summer Book (Sommarboken, 1972) notably, is a delicate and deft evocation of a summer spent on an island.

The narrative charts the relationship between a grandmother and granddaughter, and at the same time probes such profoundly human questions as love and loss, hope and change and continuity. As always in Jansson, the descriptions are sharp and crisp, and the writing is at once spare and suggestive.

Novels like Fair Play (Rent spel, 1989) and The True Deceiver (Den ärliga bedragaren, 1982) reveal Jansson’s subversive, sly, and subtle sides, which sit alongside her playfulness, warmth, and humour to create a unique aesthetic. Fair Play is a book about the relationship between two women; it’s tender, funny and thoughtful. Never sentimental, it is nonetheless moving. And it’s quietly subversive in its matter-of-fact depiction of a same-sex relationship.

The True Deceiver is set in a snowbound hamlet. A young woman fakes a break-in at the house of an elderly artist, a children’s book illustrator, and a strange dynamic develops between the two women. It’s a book about being outside, about not belonging. The relationship between the women, which is never fully resolved or explained, is especially fascinating.

Jansson excels at showing the human need for both company and privacy, intimacy and autonomy. And her work is profoundly philosophical. In very light, nimble narratives, Jansson explores the meanings of our lives.

Moomin food

19 August 2010 | In the news

A cookbook that introduces Tove Jansson’s famous Moomin family and other characters from the delightful classic stories for children (and adults), with original illustrations and quotations from the Moomin books, has been published in the UK.

Entitled Moomins’ cookbook. An introduction to Finnish cuisine (translated by David Hackston and published by SelfMadeHero), the book was compiled and written by Sami Malila and published in Finnish in 1993 (WSOY).

The Moomins are also currently being celebrated in an exhibition at the Design Shop UK in Edinburgh, entitled ‘And the World Went Mad for Moomins’. The exhibition runs until September 5.

Translations of books by Tove Jansson (1914–2001) have been published in more than 30 languages.

The cookbook offers recipes of healthy porridges and fish dishes, mushrooms and fresh berries, as well as treats like one of the Moomins’ favourites, pancakes (often cooked in the oven) with jam and whipped cream.

And as this is a cookbook for the whole family, Moominpappa’s grog contains no alcohol – but it’s no secret he enjoys a drop of good whisky (see the picture) every now and then, and a good cigar.

Dark, cold – yet happy?

27 August 2010 | This 'n' that

In the fields of education, health, quality of life, economic dynamism and political environment, the best country in the world is… Finland.

In the fields of education, health, quality of life, economic dynamism and political environment, the best country in the world is… Finland.

According to the American Newsweek magazine (August 15), Finland is now the best place to live – if you appreciate the factors of life mentioned above. On the list of a hundred countries, Switzerland and Sweden were numbers two and three. More…

Jansson’s temptations

27 November 2009 | This 'n' that

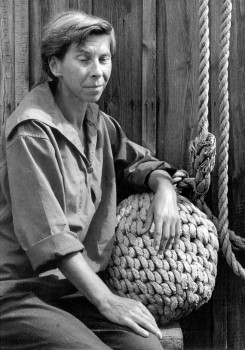

Tove Jansson (c. 1950)

If Tove Jansson’s Moomin books are, as we certainly believe here at Books from Finland, strangely little known in the wider world, the same is even truer of her books for adults.

Incredibly, the Moomins celebrate their 65th birthday in 2010, and have been translated into 40 languages. Jansson (1914–2001) wrote her last Moomin book – there are nine altogether – in 1970. Over the last thirty years of her life, she also wrote a total of 11 volumes – novels and short stories – for grown-ups. (Books from Finland published stories from many of them as they appeared. They will become available again as our digitisation project gets underway; meanwhile, here’s a story from Dockskåpet [‘The doll’s house’, 1978].)

Back out there in the wider world, the tiny, Hampstead-based press Sort Of Books has since 2001 been introducing Jansson’s lesser-known works to British readers. Latest to appear is her bleakly unsettling novel The True Deceiver (Den ärliga bedragaren, 1982), the story of a strange young woman, Katri, who breaks into an elderly artist’s house and attempts to befriend her, for reasons of her own. More…

Ice hockey and grumpiness – popular books in September

16 October 2014 | In the news

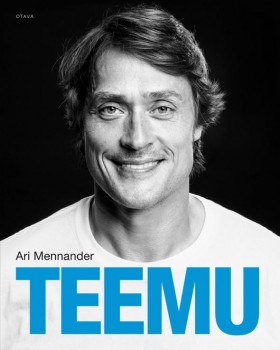

Ice hockey veteran: Teemu Selänne

The September list of best-selling non-fiction compiled by Suomen Kirjakauppaliitto, the Finnish Booksellers’ Association, included books on mushrooming: a popular pastime that, finding fungi for dinner. However, number one was the biography of the most internationally successful (NHL) ice hockey player so far, Teemu Selänne (recently retired), entitled Teemu (Otava).

Ilosia aikoja, Mielensäpahoittaja (‘Happy times, you who take offence’, WSOY) is the third book in the popular humorous series by Tuomas Kyrö, and it tops the September list of the best-selling Finnish fiction.

Kyrö’s protagonist, this mielensäpahoittaja, the one who ‘takes offence’, is a 80-something grumpy old man living in the countryside and opposing most of what contemporary lifestyles are about. For in the olden days everything was better: for example, food wasn’t complicated and cars were easily repairable.

Apparently Finns can’t get enough of this grumpiness. What began as short monologues written for the radio has become a series of books, and Kyrö’s Mr Grumpy has also appeared on the stage as well as on the screen: the first night of the film, also entitled Mielensäpahoittaja (directed by Dome Karukoski), took place in September. Will there be much more to come, we wonder.

Number two was the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes (pseudonym) with a book entitled Horna (‘Hell’, WSOY), and on third place was the new book by Anna-Leena Härkönen, a novel about a married couple who become lotto winners, Kaikki oikein (‘All correct’, Otava).

First place of the best-selling books for children and young people was occupied by the Moomins – not the original story books or comics by Tove Jansson though, but by other ‘Moomin writers’ and illustrators, whom there have been surprisingly many after Jansson’s Moomin art was made reproducible; this time the book is entitled Muumit ja ihmeiden aika (‘The Moomins and the time of wonders’, Tammi). Another cause of wonder, we think.

To write, to draw

18 December 2014 | This 'n' that

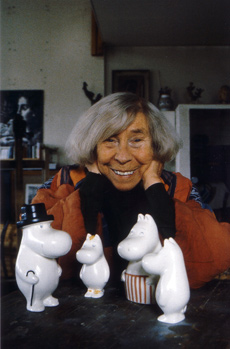

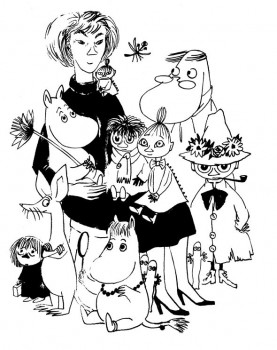

Self-portrait: Tove Jansson with her creations. Picture: @Moomin Characters™

A new Finnish biography of Tove Jansson (1914–2001) was published in 2013; the artist and creator of the Moomins has been celebrated in 2014 in her centenary year. Tove Jansson. Tee tytötä ja rakasta by Tuula Karjalainen was published in English this autumn, translated by David McDuff, under the title Tove Jansson: Work and Love (Penguin Global, Particular Books).

The book was reviewed by The Economist newspaper on 22 November. Unsurprisingly, according to the review, Jansson was more interesting as a writer than as a painter:

’Jansson always saw herself first as a serious painter. She exhibited frequently in Finland, and won awards and commissions for large public murals. Her reputation there as a writer lagged far behind the rest of the world. Ms Karjalainen is a historian of Finnish art, and although she covers Jansson’s writing, it is the paintings that really interest her. This is a pity. Jansson was a more interesting writer than a painter, and her life sheds much light on her particular quality as a storyteller.’

Whereas Karjalainen concentrates on Jansson’s painting, another biography of Jansson, by the Swedish literary scholar Boel Westin (reviewed here) focuses on Jansson as a writer. Here, you can find a selection of Tove Jansson’s art.

A quotation from The Economist‘s review: ‘Her use of Moomins to defy the war is characteristic. Everywhere in her fiction there is the same sense of deflection and indirection. She hated ideologies, messages, answers. And it somehow fits that she fell in love with both men and women. Ambivalence was a kind of comfort to her. As one of her characters says, “Everything is very uncertain, and that is what makes me calm.’

Tove Jansson’s versatile brilliance as an artist, we think, is at its best in the way she combined illustration and text in her Moomin stories. Their (great) visual and philosophical value lies in the praise of freedom and independence of the mind: for everyone, young or old.

Looking for Moominpappa

30 June 1994 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

Tove Jansson wrote the first Moomin book in the dark days of Finland’s Winter War in 1939. This extract, from Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (‘The little trolls and the big flood’, Schildts, 1945, 1991), tells the story of how the Moomins found their home

It had become very hot late in the afternoon. Everywhere the plants drooped, and the sun shone down with a dismal red light. Even though Moomins are very fond of warmth, they felt quite limp and would have liked to rest under one of the large cactuses that grew everywhere. But Moominmamma would not stop until they had found some trace of Moomintroll’s Papa. They continued on their way, even though it was already beginning to get dark, always straight in a southerly direction. Suddenly the small creature stopped and listened. ‘What’s that pattering around us?’ he asked.

And now they could hear a whispering and a rustling among the leaves. ‘It’s only the rain,’ said Moominmamma. ‘Even so, now we must crawl in under the cactuses.’

All night it rained, and in the morning it was simply pouring down. When they looked out, everything was grey and melancholy. More…

Still selling best

8 May 2014 | In the news

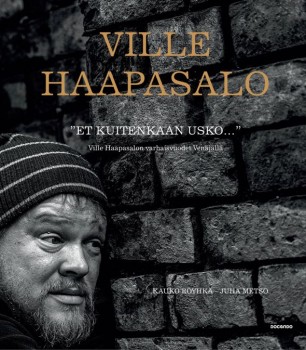

Celebrity in Russia: Ville Haapasalo on the cover of Et kuitenkaan usko… (’You won’t believe it anyway…’)

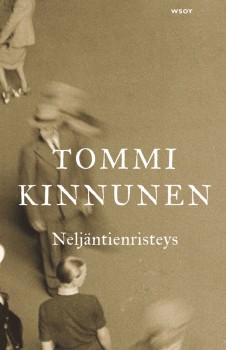

Not a lot of new titles made it to the list of the best-selling books – compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association – in April, it seems. Number one on the Finnish fiction list was still Tommi Kinnunen’s first novel, Neljäntienristeys (‘The crossing of four roads’, WSOY).

In March this title reached the top after favourable reviews – in the Helsingin Sanomat daily paper in particular. The narrative spans a century beginning in the late 19th century and takes place in the Finnish countryside.

Number two – again – was another first novel about problems arising in a religious family, Taivaslaulu (‘Heaven song’, Gummerus, 2013) by Pauliina Rauhala. Number three was the latest crime/police novel by Seppo Jokinen, Mustat sydämet (‘Black hearts’, Crime Time).

On the translated fiction list, after George R.R. Martin’s A Dance with Dragons – top of the list in March too – is Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. Another donna (Donna Leon) was number three with her Beastly Things.

On the non-fiction list number one was a book on the Finnish actor / television journalist Ville Haapasalo’s life – and adventures during his travels in Russia, where he is a big celebrity and film star – by Haapasalo, Kauko Röyhkä and Juha Metso (Docendo). Number two was an autobiographical book by Katri Helena, a pop star who began her career in the 1960s.

The selection among the 20 best-selling books included, as usually, autobiographies and biographies, cookery, books about birds and nature. And Moomins. Books about Moomins and their creator Tove Jansson (1914–2001) certainly will rule this year – Jansson’s centenary.

Remembrance

29 March 2014 | This 'n' that

This year is the centenary of Tove Jansson (1914–2001), the painter, caricaturist, comic strip artist, illustrator and author of books for both children and adults, and, what made her name internationally, the creator of the Moomins. Today, her Moomin books are available in 40 languages.

This year is the centenary of Tove Jansson (1914–2001), the painter, caricaturist, comic strip artist, illustrator and author of books for both children and adults, and, what made her name internationally, the creator of the Moomins. Today, her Moomin books are available in 40 languages.

One sunny April day, walking through the atmospheric old Hietaniemi cemetery by the sea in Helsinki, a charming little bronze statue on top of a narrow granite column caught my eye.

Family grave: sculpture by Victor Jansson

It was a small child balancing on a ball, waving its arms and legs joyously in the air. On a closer look, there was something white attached to the statue: it was a tiny white plastic Moomin.

On the Janssons’ family grave the first little blue flowers had just risen to the surface to bask in the early spring sun. Tove’s father was the sculptor Victor Jansson, her mother was the cartoonist and artist Signe Hammarsten Jansson.

Perhaps one of Tove’s fans had chosen this way of paying homage to the creator of the unique Moomin universe.

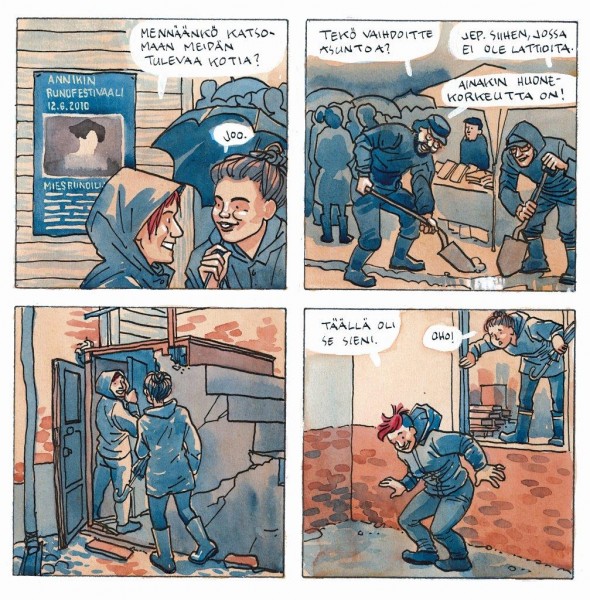

Picture this

9 April 2015 | Articles

It’s impossible to put Finnish graphic novels into one bottle and glue a clear label on to the outside, writes Heikki Jokinen. Finnish graphic novels are too varied in both graphics and narrative – what unites them is their individuality. Here is a selection of the Finnish graphic novels published in 2014

Graphic novels are a combination of image and word in which both carry the story. Their importance can vary very freely. Sometimes the narrative may progress through the force of words alone, sometimes through pictures. The image can be used in very different ways, and that is exactly what Finnish artists do.

In many countries graphic novels share some common style or mainstream in which artists aim to place themselves. In recent years an autobiographical approach has been popular all over the worlds in graphic novels as well as many other art forms. This may sometimes have led to a narrowing of content as the perspective concentrates on one person’s experience. Often the visual form has been felt to be less important, and clearly subservient to the text. This, in turn, has sometimes even led to deliberately clumsy graphic expression.

This is not the case in Finland: graphic diversity lies at the heart of Finnish graphic novels. Appreciation of a fluent line and competent drawing is high. The content of the work embraces everything possible between earth and sky.

Finnish graphic novels are indeed surprisingly well-known and respected internationally precisely for the diversity of their content and their visual mastery.

Life on the block

Favour and fame: becoming a best-seller

10 April 2014 | In the news

At the top of the list of best-selling books – compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association – in March was the first novel by Tommi Kinnunen, a teacher of Finnish language and literature from Turku. In Neljäntienristeys (‘The crossing of four roads’, WSOY) the narrative spans a century beginning in the late 19th century and is set mainly in Northern Finland, focusing on the lives of four people related to each other. Undoubtedly well-written, it continues the popular tradition of realistic novels set in the 20th-century Finland.

At the top of the list of best-selling books – compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association – in March was the first novel by Tommi Kinnunen, a teacher of Finnish language and literature from Turku. In Neljäntienristeys (‘The crossing of four roads’, WSOY) the narrative spans a century beginning in the late 19th century and is set mainly in Northern Finland, focusing on the lives of four people related to each other. Undoubtedly well-written, it continues the popular tradition of realistic novels set in the 20th-century Finland.

Finland is a small country with one exceptionally large newspaper, Helsingin Sanomat (read by more than 800,000 people daily). The annual literary prize that carries the paper’s name is awarded to a best first work, and candidates are assessed throughout the year.

In February the paper’s literary critic Antti Majander declared in his review of Kinnunen’s book: ’Such weighty and sure-footed prose debuts appear seldom. If I were to say a couple of times in a decade, I would probably be being over-enthusiastic. But let it be. Critics’ measuring sticks are destined for the bonfire.’ More…